For 49 days in 1963, 21-year-old Helen Klaben lived trapped in the Yukon wilderness in the dead of winter with multiple broken bones, no food, and no winter survival equipment or training. She would not have survived a 50th day. She would have succumbed to hypothermia or death by starvation, her withered, frozen body eventually found and consumed by one of the wild animals the thoughts of which had terrified her for the past 7 weeks.

Klaben never had to face that 50th day after being rescued by the very thing that got her into that mess—a solitary single-engine plane flying low over the Alaskan bush.

She’d left her rented dwelling in Fairbanks at the end of January destined for San Francisco and after that, she’d hoped, a long sightseeing tour through Asia. Klaben was a native Brooklynite with a serious case of wanderlust. She left New York at 20 for the dimmer lights but grander vistas of Alaska. After driving across North America, she spent a few months working for the Bureau of Land Management and taking classes at the University of Alaska.

Tiring of that and getting the hell out before a proper winter descended on Alaska, Klaben decided to head for Asia. In Fairbanks she’d met a 41-year-old plane mechanic from California named Ralph Flores and he agreed to fly her to San Francisco if they split expenses. Flores wasn’t a very good pilot. He couldn’t fly by instruments alone, kinda a dealbreaker if you want to fly in the chaotic weather in Alaska. He was an even worse planner, forgoing so much as an extra parka in the plane; the aircraft lacked even the most basic winter survival equipment.

Nevertheless, the pair flew the first leg to Whitehorse without incident. On February 4th they took off bearing south but almost immediately hit snowstorms that blinded Flores who desperately tried to climb above the clouds; when that didn’t work he descended to get close enough to the ground to navigate by roads. Instead, he flew into a mountain.

“We were flying by a mountain and I saw trees right below us,” Klaben told a reporter. “I knew we were going to crash.”

“I said out loud, ‘O.K., Helen, here it comes,’” remembered Flores. “I saw the right wing tip hit the trees and I just closed my eyes.”

The plane dumped into a deep snow drift and was ensnared in trees. Klaben’s right foot was crushed and her left arm was broken. Flores had a banged up face but was otherwise okay. For the next ten days they awaited rescue huddled in the wreckage, rationing the few cans of sardines and tuna he’d brought along with some crackers. When the food ran out, the two allowed themselves a capful of toothpaste hoping to metabolize something in it into energy. They melted snow, poured it into makeshift bowls, closed their eyes, and conjured the smells of rich tomato soup, a hearty beef noodle, or a thick, decadent New England clam chowder.

Flores spent much of his time trying to convert Klaben from Judaism to Mormonism. She mostly read books.

After a month, Flores, who’d taken to wandering the woods in self-made snowshoes, reported he’d found a clearing nearby that would allow more chance for aircraft to spot them. Klaben at that point was developing gangrene in her busted foot and frostbite had set its icy talons into her toes. She struggled the kilometer or so to the new camp and collapsed. Exhausted and malnourished she’d lost 40 pounds already. Flores too was losing weight rapidly, but he constantly worried about how alarmingly think Klaben was. She gets the toothpaste, he decided.

En route to the clearing, a feint, far off mechanical hum started to reverberate through the snow-covered trees. After they set up camp, Flores snowshoed off toward the sound and a beaver pond he saw through the trees. Figured he could stamp out SOS on the frozen pond, maybe get a better ear on that noise too.

On March 24, a bush pilot named Chuck Hamilton took off from Watson Lake, in far northern British Columbia. He climbed, and began sweeping over the trees looking for game. After a few minutes he passed a frozen pond marked with an unmistakable SOS.

At camp, Klaben looked up from her book to see Hamilton’s plane droning overhead. She hobbled to their fire and dumped an armload of pine boughs to throw up a column of smoke. The plane passed through it, registering the location, then headed down the mountain only to see a winking light in the snow; it was Flores signaling them with a mirror. Hamilton brought the plane down at a trapper’s cabin he saw; the trappers were outside cutting wood with a chainsaw—the sound Klaben and Flores had been hearing.

Though Klaben and Flores were all over the news when their plane disappeared and Hamilton had heard the story, that was six weeks ago, long enough for him and everyone else to assume the pair was dead. It didn’t even occur to him the SOS was from them until he flew back to check out the signal fire again. This time when he passed over it, he could see the plane’s wreckage and the ID number—it was Flores’s wreck.

But it was nearing nightfall and Hamilton couldn’t land there. He flew home, discovered the trappers had gone out and plucked Flores from the forest, so he was safe. But all night, Hamilton anguished over the Klaben girl. He decided to fly up in the morning to land as close as he could.

The dawn broke clear as a bell and miraculously warm. Hamilton decided Klaben likely lived through the relatively comfortable night and began winging toward the fire he saw. He landed in an open space three kilometers away and trudged toward the smoke. There sat Helen Klaben, a beaming smile on her sun-blasted emaciated face.

“Come here, I’ll give you a big kiss,” she shouted.

Later that day, Klaben safely in medical care, clouds blew in, snow began to dump and the temperature plunged to well below zero. The SOS message was buried. Flores was convinced she wouldn’t have lived another night.

Though the FAA suspended Flores’s license for a year because he failed to pack the plane with survival gear when flying in harsh winter conditions, Flores and Klaben remained friends in the years to come.

Flores died in 1997. Klaben in 2018.

“Most people expect they would not be able to cope with a crisis,” Klaben later told People magazine. “It was a great experience to find out that I could.”

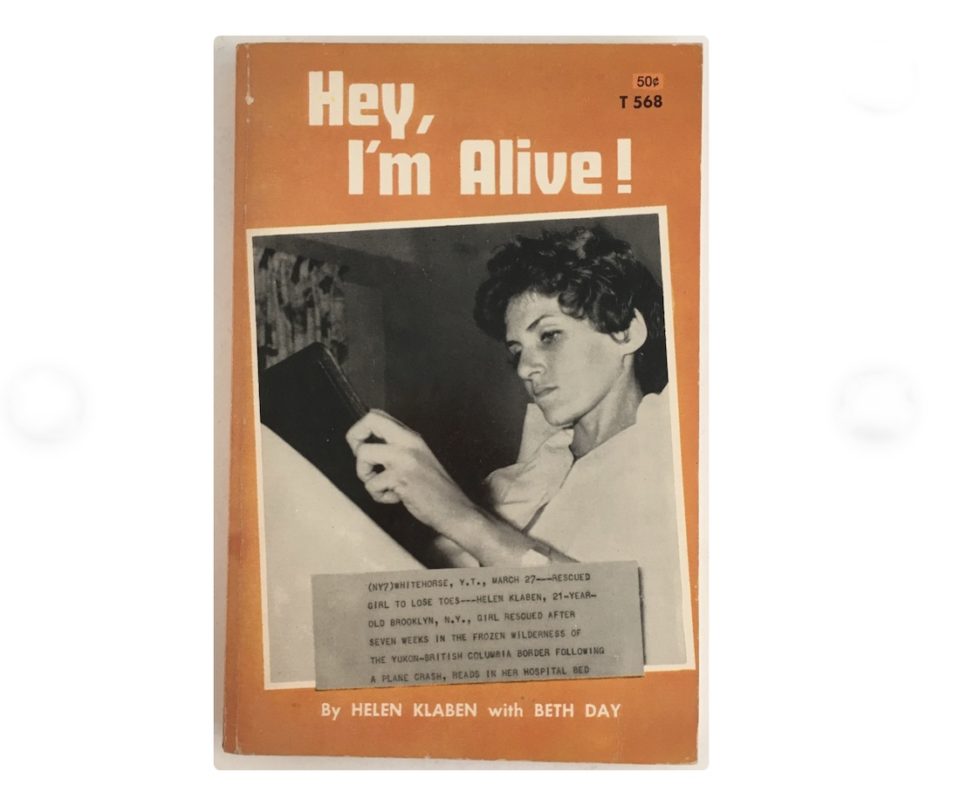

Klaben wrote a book about the ordeal called “Hey—I’m Alive!” that was turned into a Sally Struthers film in 1975 of the same name.

Source : adventure-journal