With usage skyrocketing on America’s public lands, the Bureau of Land Management this week unveiled a new initiative aimed at improving access to acreage that is unreachable or challenging to reach because of land ownership patterns and other obstacles.

Public land doesn’t serve the greater good if hunters, anglers, campers or other users can’t get to it, BLM Director Tracy Stone-Manning said.

“I’m really excited about the work, because it turns out we’re going to need more space,” Stone-Manning told WyoFile Sunday in Casper, where she spoke at the Outdoor Writers Association of America conference. “We can’t make any more land, but we can open up the land and we’re gonna need that space because people are coming.”

The BLM Dingell Act Priority Access List Portal, which launched in May, does two things. First, it highlights 712 parcels of public lands (whittled down from upwards of 6,000 originally nominated) that have been identified for access improvements. The parcels cover about 3.5 million acres in 13 Western states, including Wyoming. The 2019 John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act, which contains provisions aimed at preserving public access through civic engagement, enabled the initiative.

“This list is going to help guide our acquisition strategy for years to come, helping us prioritize acquisitions using the Land and Water Conservation Fund and other sources to truly move the needle on public access,” Stone-Manning said.

The portal also allows users to nominate parcels they want considered for future access improvements.

A recent report by the backcountry GPS app onX identified more than 9 million acres of federal public lands in Western states with no permanent legal access — the vast majority under BLM management. Of those, the report said, some 3.05 million are in Wyoming, where a checkerboard pattern of alternating land ownership has created high-profile conflicts over what’s known as corner crossing.

Bureau of Land Management Director Tracy Stone-Manning.

Bureau of Land Management Director Tracy Stone-Manning.

“We’re working hard to open access to these lands,” Stone-Manning said of the portal’s identified parcels, “connect and consolidate them into contiguous blocks open to the public, working with partner organizations and relying on our very best tool, funding from the Land and Water Conservation Fund.”

The impact of acquiring lands in the right places can be exponential in certain cases, Stone-Manning said. “So for example, if we pick up 100 acres, we might open up 10,000 behind it.

“And that’s the key, identifying the acquisitions that will provide the most impact for both people and the health of the landscape,” she said.

Stone-Manning, who was confirmed to helm the agency in late 2021 following four years with no leader, sat down with me to talk about energy development, growing recreation and wildlife concerns in Wyoming — where BLM manages more than 18 million surface acres and 42.9 million acres of mineral estate. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

KK: BLM Wyoming is No. 1 in federal gas production No. 2 in federal oil production. How is the BLM contemplating the balance between management for energy production and the Biden administration’s directive to transition to a clean-energy economy?

TSM: I see the job of transitioning to a clean energy future as something to take with great care and trepidation. Wyoming helped power the nation. The revenue structures are built around that. We need to work very closely with states so we don’t leave any communities behind. But we also have to be clear about the fact that a transition has to occur, and a transition will occur. The market is driving a transition at this point. Wyoming will continue to be a big energy producer, I’m sure, given the wind resource here. And it was beautifully sunny today. We just need to be thoughtful about what that transition looks like and try to keep cultural politics out of it as much as possible as we think very carefully about market needs, business needs, community needs and needs of the future.

How will the BLM ensure that neither fossil fuels nor renewable energy negatively impact wildlife habitat and cultural resources?

We have 245 million acres in our care on behalf of the American public, and our job is to make sure we pass these lands down to future generations in better shape than we found them. And yet, scientists are telling us that we stand to lose a third of our wildlife if we don’t take some pretty big measures. And scientists are telling us that climate change is among us — we don’t need scientists to tell us this, living in the West we can see it. So part of the work now is to really get smart about building climate resilience and conservation into everything we do.

And part of that is taking advantage of things like the bipartisan infrastructure law, $900 million coming to the Department of Interior for restoration, putting people to work on our public lands, attacking things like cheatgrass, getting healthy grasslands back into place, which then better withstand the fire regime that is among us.

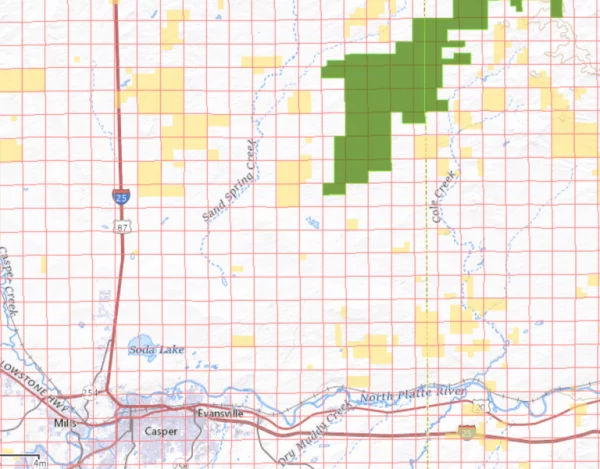

The BLM’s newly launched Dingell Act Priority Access List Portal allows users to nominate land parcels they want considered for improved access. Users can also view BLM-identified parcels, such as the Sand Hill parcel near Casper, seen in green. (Screenshot/Bureau of Land Management

In Wyoming one of the main species that conflict could happen with is sage grouse. BLM oversees more of the bird’s habitat than any other federal agency. What measures are the BLM contemplating as it updates the grouse management blueprint adopted in 2015 in light of data indicating decline?

We’re not gonna be able to do it without the states being right at the table with us. And with understanding and sign-off from the communities in which we work. Again, that’s just sort of hard clear-eyed work of, ‘here’s where the data was in 2015 and here’s where it is in 2022. And so we think that that data in 2022 is pointing us in fill-in-the-blank direction.’ Folks are still doing that work. I don’t have the direct answer for you because I don’t know how [data are] going to change.

It comes back to the whole notion of the way I approach this work, which is when you’re managing for a healthy landscape, the rest falls into place. It falls into place for people, it falls into place for wildlife, it falls into place for our economy.

When you talk about getting communities to the table, what does that look like?

It’s through sitting down with governor’s offices and state fish and game departments and good smart people who know what they’re doing. Wyoming has helped lead the way on sage-grouse conservation. It’s [the state] saying, ‘OK, this is what we’re seeing.’ Then when we have a draft plan, we go to the communities at large and say, ‘What do you think?’ And ask for serious engagement and feedback to help drive the final decision.

Recreation is growing across the West and in Wyoming. How does BLM envision striking a balance between growing demand and preservation of the resources, and do you see it as a promising economic engine?

Recreation is a giant economic engine already across the West, and that’s only going to continue to grow. First, people come here to recreate, second, as we just saw in the pandemic, people have realized, ‘oh wait, it’s a great place to live.’ People are moving here in droves. And that’s creating all kinds of issues in communities with housing prices going through the roof, but it’s also creating a responsibility for us with increased recreation on the lands we manage. And so we have our work cut out for us. Over 80 million people visited BLM lands last year. That quickly snowballs into something that’s out of our control.

Encompassing over 100,000 acres, the Killpecker Sand Dunes in the Red Desert is one of the largest sand dune areas in the world. Boar’s Tusk, the remains of a volcano, can be seen in the distance. (Bob Wick, BLM/FlickrCC)

The BLM’s Rock Springs Field Office has long been expected to release revisions to its Resource Management Plan, which covers the Red Desert. Do you have any update on where this process is?

They are not going to have to wait past this administration. I’ve talked to the folks in the Rock Springs Field Office. I made a commitment to them that we are going to get this thing out the door.

Western Watersheds Project says the BLM has been skipping environmental reviews on grazing permit renewals for years, leading to the degradation of millions of acres of public lands. Can you speak to that claim or anything the BLM is doing to address it?

Congress did pass legislation that enabled people to get extensions on their permits without doing NEPA. And it’s not OK. It’s just not OK that some producers out there are working on 20-year-old permits. Because they know that their permit no longer suits the conditions on the ground, right? So I am hoping that the grazing rule updates that we’re hoping to get across the finish line will build the flexibility into the role that they need, and the landscape needs and that we need to help us get out of this landscape health issue.

Should BLM corner-crossing guidelines be revised in light of the not guilty verdict in the Carbon County case?

What’s interesting to me about corner crossing is the deeply held values that underlie it. And I’m really interested, in light of this case, in digging in and taking a deeper look. I know the agency has had different opinions across the decades about this issue. And the last opinion that we had was issued in 1997.

A large wild horse roundup took place in southern Wyoming in 2021. The BLM this month announced fertility control efforts. Can you tell me about the strategy for finding solutions for managing the health of herds and public lands in what many would say is an intractable problem?

At times it feels intractable, in part because it’s a species on the landscape that didn’t evolve with the landscape and therefore doesn’t have a natural predator. And so unless we manage them, unless we pull some horses off the landscape, or figure out very quickly long-term fertility control, the populations double every four years. And that is untenable. It’s untenable for the horses, it’s untenable for the landscape, it’s untenable for wildlife.

This article was first published by WyoFile and appears here with permission.

Read more :

- Are User Fees a Fair Solution for Public Lands Management?

- When Recreationists Have Too Much Clout on Public Lands

- The Biggest Public Lands Bill in a Generation Is About to Become Law

- An Updating Record of COVID-19’s Impacts—From Public Lands to Retail Closures

- Hike the Hill 2020 Urges Motion on Out of doors Entry, LWCF, Public Lands Upkeep, and Trails

- Would You Help Opening Non-public Land to Accountable Public Entry?

- Unlawful Weed Farms are Poisoning Our Public Lands

- Meet The Man Who Visited All 478 Federal Public Land Properties

- E-Bikes on Public Lands? Not so Quick, Say These Conservancy Teams

- Inside a Essential Battle Over Water Rights Beneath Public Lands

- Inside a Essential Battle Over Water Rights Under Public Lands