I approached this review with a fair bit of skepticism.

Any book whose title includes “Yeti Presents” deserves a dose of scrutiny, even if the subject it is presenting — Whitewater — is a topic of boundless potential and great personal interest.

Also, I should disclose that this review came with a junket attached – an expenses-paid trip down Westwater Canyon on the Colorado River that would start with gourmet tacos and tequila and end with a dozen hypothermic writers huddled in the rafts as 65-mile-per-hour gusts ripped up-canyon.

Good Type-2 fun, but I digress. A few days after I told the gregarious young flack to count me in, a box arrived, filled with a stainless steel beer coozy, a Yeti-branded branded sun hat and—nice touch—a blue NRS camstrap.

All this was nestled around a hardcover tomb inscribed with one magic word, Whitewater.

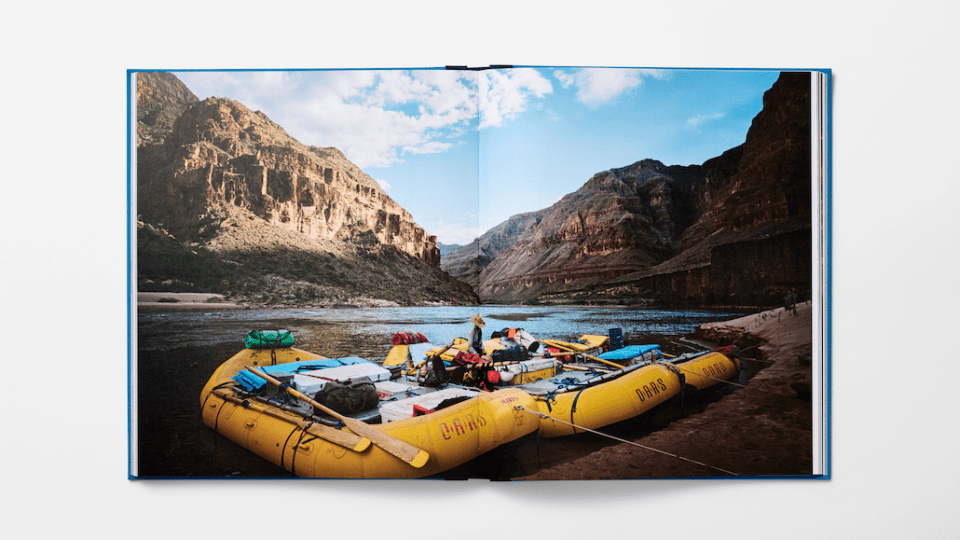

Inside, on 156 luscious pages printed in Italy, were hundreds of photographs and six essays from writers I have long admired. The photos were an eclectic mix of portraits, still life and whitewater action of every kind: Rafts punching hungry holes, dories dancing through muddy froth, kayaks launching from picturesque waterfalls. The editorial team, led by Grand Canyon swamper turned Emerald Mile author Kevin Fedarko, clearly took an expansive view of the subject at hand.

The book is full of knowing references to the culture of moving water, and stuffed with cameos of river-running heroes young and old. The doryman-conservationist Martin Litton glares from one page, his visage a silent admonition to fight for places we hold dear. Daredevil Al Fausset poses with the hollow log on which he rode through Eagle Falls, seeking a fortune that never materialized.

The younger generations are represented too—Scott Lindgren and Gerry Moffat in the depths of the Grand Canyon of the Stikine; Rush Sturges in the Pacific Northwest, Rafa Ortiz in Mexico, and a dizzying image of Knox Hammack on the cusp of 189-foot Palouse Falls.

You could spend hours just soaking in the images, which I suppose is the point of a book that will hold King Of The Mountain status on boaters’ coffee tables for years. The real depth, though, is in the essays, each of which deconstructs a particular aspect of whitewater: the scout, the entry, the crux, and the run-out.

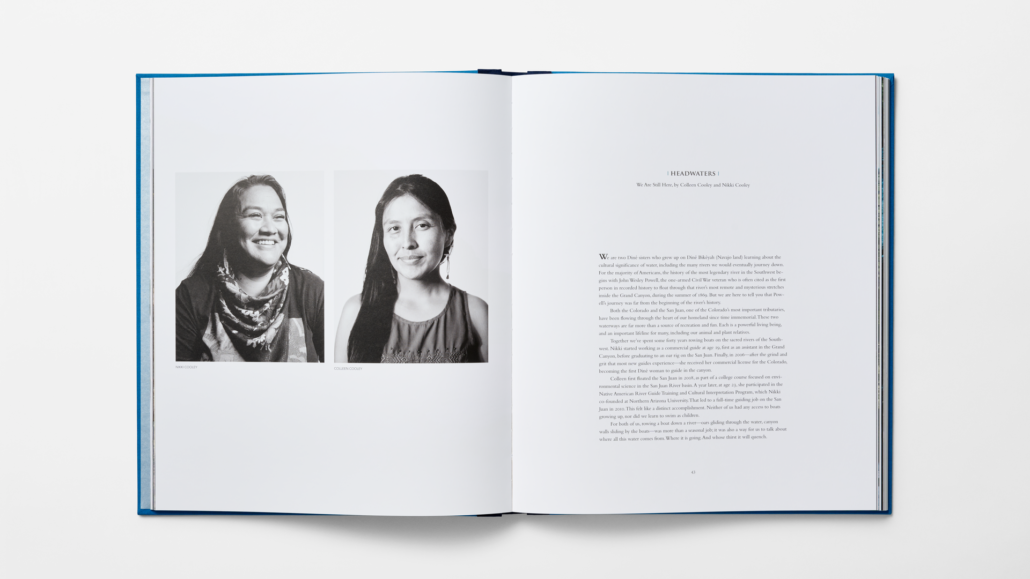

Nikki Cooley was the first Diné woman to guide in Grand Canyon, and her sister Colleen followed her into the profession despite neither having learned to swim as children growing up in Navajo Nation. Their essay, Headwaters, starts us off with some much-needed context. “Both the Colorado and the San Juan, one of the Colorado’s most important tributaries, have been flowing through the heart of our homeland since time immemorial,” the sisters write. “These two waterways are far more than a source of recreation and fun. Each is a powerful living being an important lifeline for many, including our animal and plant relatives.”

Next Zak Podmore (who, more disclosure, is a friend and former colleague) describes the Scout, the process of anticipation, visualization, self-doubt and internal pep-talk that, as he puts it, happens before anything has happened. “It takes place in an ethereal space of possibility somewhere or sometime before the actual has had its say. And it reminds us that for all of our attempts to stay in control, life is most vibrant when it breaks through to the unforeseen.”

These are essays you’ll read in five minutes, and think about for days.

Pam Houston, whom a reviewer once called ‘the rodeo queen of American letters,’ delivers a heartfelt paean to the ‘V-slick’ — the smooth-flowing ramp of water at the entrance of a big-water rapid—noting that the position of one’s boat when it reaches that downstream V determines the success or failure of the enterprise.

Diné raft guide sisters Nikki and Colleen Cooley. “We should all be fortunate enough to experience and respect the grandeur of a powerful life force streaming not only through our veins, but through our homeland,” they write.

In his essay, Craig Childs tackles the subject of Chaos, reflecting on the nature of water and the conflicted approach so many river-runners have toward its varied moods. “You’d think with how nervous I get around whitewater I’d avoid it. Not the case. I want what water wants. I want every state.”

Mark Sundeen wraps up with an essay on Eddies, those quiet backwaters that “transform hostile rivers into human habitat.” In his case, they also provide a trio of unforgettable anecdotes, at once funny and illustrative of what makes whitewater so irresistible to those who choose to make their lives in and around moving water.

The attraction is hard to put into words, though Fedarko does better than most. Recalling the aftermath of a bad line at Horn Creek in Grand Canyon, he writes, “Sometimes that’s the way whitewater works. Fail to discern where the current wants to go, where it’s actually heading (which is not necessarily the same thing) and where your boat has to be in order to thread the needle between those competing vectors, and the river will knock you into next week.

“But every now and then, in the process of slapping you away from where you were hoping to go, the current delivers you to the place that you really need to be, even if at the top of the rapid, you didn’t fully understand how to get there.”

A limited edition of Whitewater is also now available through American Rivers’ website. All proceeds will go to American Rivers, and a purchase enters you into a drawing to win a 17-day OARS trip for two on the Grand Canyon.

Top Photo: Martin Litton during his last run of Lava Falls, at age 93. Photo: John Blaustein

Read more :

- The Greatest Grand Canyon Speed Runs, Ranked (Not By Speed)

- Pioneering (and Obsessive) Grand Canyon Explorer Harvey Butchart

- The First Canoe Self-Help Of Grand Canyon Simply Occurred, And It Was A Ball

- Chilly Arms, Sleep Deprivation, and the Quest for a Grand Canyon Pace File

- Shock Typewriter Let Hikers Peck Out Love Notes to Grand Canyon

- The place Did the Time Go? Grand Canyon Nationwide Park Turns 100

- Grand Canyon National Park – Journey From ‘Worthless’

- The 10 best long-distance hikes in the US in 2022

- The 8 Best Long-Haul Backpacking Trails in USA for 2022

- Grand Canyon Nationwide Park Has a New Junior Park Ranger—And She’s 103

- The best travel destinations for LGBTQ+ travellers in 2022