In June 1802, midway through his five-year scientific exploration of Spanish America, Alexander von Humboldt set out to climb Chimborazo, a 20,564-foot volcano in Ecuador’s Cordillera Occidental. At the time, it was thought to be the highest mountain in the world (a claim recently thrown back into contention by scientists measuring from the center of the earth).

Humboldt started up the mountain at the head of a party of seven, which was soon reduced to four. “The Indians who were accompanying us had left, saying that we were trying to kill them,” Humboldt recalled in a letter to his brother. They slogged onward: Humboldt, the French botanist Aimé Bonpland, Ecuadorean hidalgo Carlos de Montúfar, and an unnamed servant loaded down with instruments. Lacking even the most basic climbing gear, the quartet continued their ascent, at times crawling over knife-edged sections on all fours. Humboldt noted his lack of mental acuity which he correctly attributed to the lack of oxygen at altitude, but it was a 60-foot crevasse that finally stopped them. Not even Humboldt could envision a way around it. Even so, the group had climbed higher than any European in recorded history, reaching 19,286 feet by Humboldt’s careful calculations (Incas had climbed higher, though archeological evidence of their exploits wouldn’t surface for nearly two centuries).

Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland near the foot of the Chimborazo volcano, in an 1810 painting by Friedrich Georg Weitsch. Wikimedia Commons

It was here, on the slopes of Chimborazo, as the clouds occasioned a view of the surrounding landscape, that Humboldt was struck by the revolutionary conviction that the world was a single, web-like, interconnected organism.

Humboldt’s ideas on the natural world were a revelation. He wrote so prodigiously upon return that he later admitted to losing track of exactly how many books he’d written. (The tally reached 30 published volumes, not counting his journals from his explorations in South America, Cuba and Mexico, which ran to 4,000 pages and fetched $13.7 million in 2013. This in addition to some 30,000 letters he wrote to about 2,800 people.)

All this writing made Humboldt the most celebrated scientist of his day, and a worldwide influence on every field of scientific inquiry. Charles Darwin proclaimed him simply the “greatest scientific traveler who ever lived.”

Alexander von Humboldt was born in Berlin in 1769 to a prominent Prussian family and began exploring his natural surroundings at an early age. He was pushed academically by his precocious older brother, Wilhelm, who became a noted diplomat, philosopher and linguist in his own right.

As a young man, to appease his demanding and emotionally distant mother, Alexander studied geology and took a position as a mine inspector. In this short career, Humboldt opened a free school for miners (paid for out of his own pocket) and sought to establish an emergency relief fund for injured workers. He also devised a miner’s lamp that would work in the oxygen-poor air of the mines. Testing it marked the first of many times his scientific curiosity would nearly kill him; the lamp kept burning long after Humboldt had passed out from oxygen deprivation. A colleague “groped after me in the dark and found me unconscious next to the lamp,” Humboldt recalled.

Humboldt excelled at mining—pits under his supervision produced more gold in his first year than they had in the previous eight—but no single subject could hold his interest for long. His first book was a botanical treatise, written in his spare time and published when he was 23 years old. Next, he produced two volumes on the effects of electrical pulses on muscle movement. For this he resorted to self-experimentation, attaching electrodes to open wounds in his back and charging himself with electrical current to observe the results.

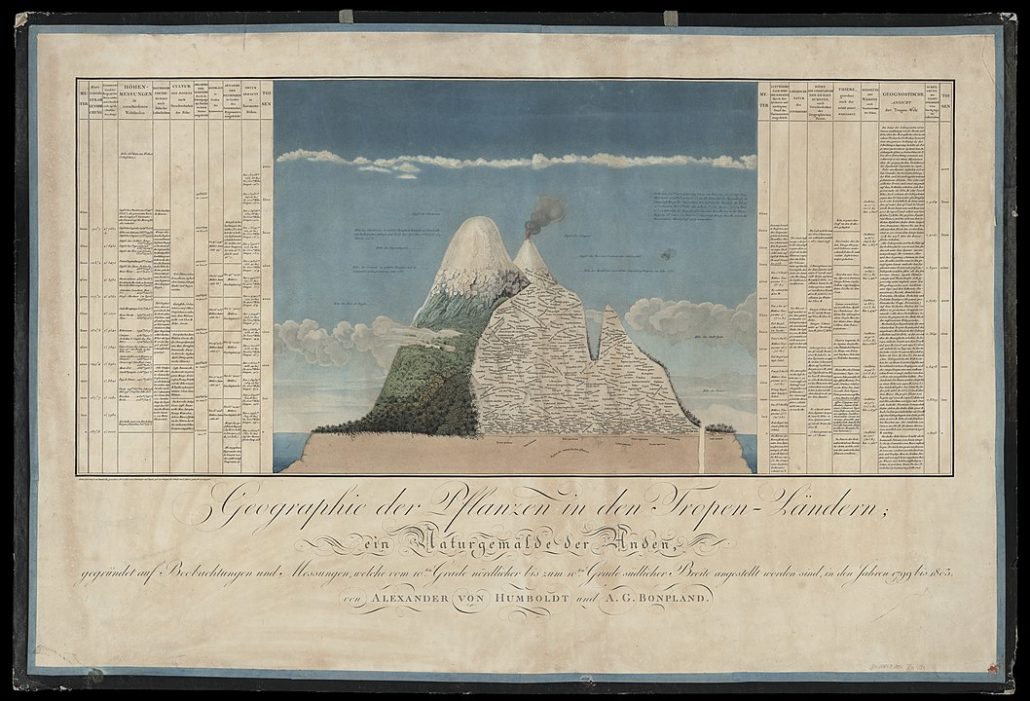

Humboldt’s Naturgemälde depicts the volcanoes Chimborazo and Cotopaxi in cross section, with detailed information about plant geography. The observations Humboldt made on Chimborazo more than 200 years ago have been used to document climate change. Wikimedia Commons

His mother’s death left him with a fortune large enough to finance his scientific adventures, and in 1799 he set out for Latin America to satisfy his curiosity about, well, everything. “I will collect plants and animals, measure temperature, the elasticity, the magnetic and electrical content of the atmosphere, dissect them, determine geographical longitudes and latitudes, measure mountains,” he wrote to his bankers. “But this is not the main purpose of my journey. My real and sole purpose will be to investigate the interconnected and interweaving natural forces and see how the inanimate natural world exerts its influence on animals and plants.”

He brought with him six oxcarts full of scientific instruments and set about measuring everything from the curvature of the earth to the blueness of the sky. Lured by the unknown, Humboldt explored the rain forests of Venezuela, the high Andes of Ecuador and Peru, the ancient ruins and contemporary economy of Mexico. At 30, Humboldt undertook his first big expedition, a 1,725-mile exploration of Venezuela’s Upper Orinoco River starting in February of 1800. He set off from the coast in a large canoe with a dog, his great friend and collaborator Bonpland, and a crew of Indigenous paddlers. For 75 days, the travelers lived on rice, ants, manioc, river water and the occasional monkey. Humboldt returned with a detailed map of the river—including confirmation of its connection to the Amazon basin—and the tale of another scientific brush with death.

To satisfy his curiosity about the biology of electric eels, Humboldt had persuaded villagers to collect hundreds of them, which they accomplished by stampeding wild horses into the river. The eels released their electrical charges on the horses (some of which drowned in the melee) allowing the villagers to scoop the depleted eels into Humboldt’s canoe with long sticks, until the wet floor of the canoe was wriggling with them. When Humboldt touched the highly charged water pooled in the hull, he received a shock so powerful it left him unconscious for several hours. The moment he came to, he asked for pen and paper to record the details of his physiological distress.

After a stay in Cuba, he and Bonplant continued on a nine-month, 1,300-mile trek through the Andes, climbing Pichincha (15,696 ft) and nearly topping out on Chimborazo before continuing to Peru in search of the sources of the Amazon. From Lima he sailed to Mexico, recording along the way the north-setting flow of cold water that now bears his name—the Humboldt Current.

Humboldt’s reports included detailed descriptions of hundreds of plants and animals never before been mentioned in the scientific literature. His work contributed to the advancement of many fields, including geology, geography, archaeology, biology, zoology, and oceanography. He broadened practiced science from mere description to examination.

Humboldt and Bonplant in an oil painting by Eduard Ender, 1856. Wikimedia Commons

To make sense of his prodigious notes—which included tens of thousands of astronomical, geological, and meteorological observations—Humboldt began connecting data points with lines, a technique he called isotherms, which we still use today. When we look at modern weather and topographic maps, we are looking at Humboldt’s isotherms.

His writings inspired world-changing thinkers, among them Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, and Darwin. His findings and scientific writings sparked the dreams and imaginations of many future scientists, geographers, naturalists, explorers and environmentalists. “How intensely I desire to be a Humboldt,” said Muir in his 20s, whose copies of Humboldt’s books, heavily annotated with notes in the margins, are on display at the University of the Pacific in California. Edgar Allan Poe dedicated his last important work, Eureka: A Prose Poem to Humboldt, and Walt Whitman kept one of his volumes on his desk as he composed Leaves of Grass.

Humboldt’s influence crossed into the political sphere as well; on his return from Spanish America in 1804 he stopped in Washington to meet the American president Thomas Jefferson, who proclaimed him “the most important scientist whom I have met.” None other than Simón Bolívar called him the real discoverer of the New World.

In the 19th century it was still possible for a highly intelligent individual to grasp the whole of scientific knowledge, because each discipline had not yet splintered off into separate domains of ever-increasing minutiae. Humboldt’s contemporary, the German writer, statesman, and intellectual Johann Wolfgang von Goethe said of Humboldt, “He knew everything, and knew everything thoroughly.”

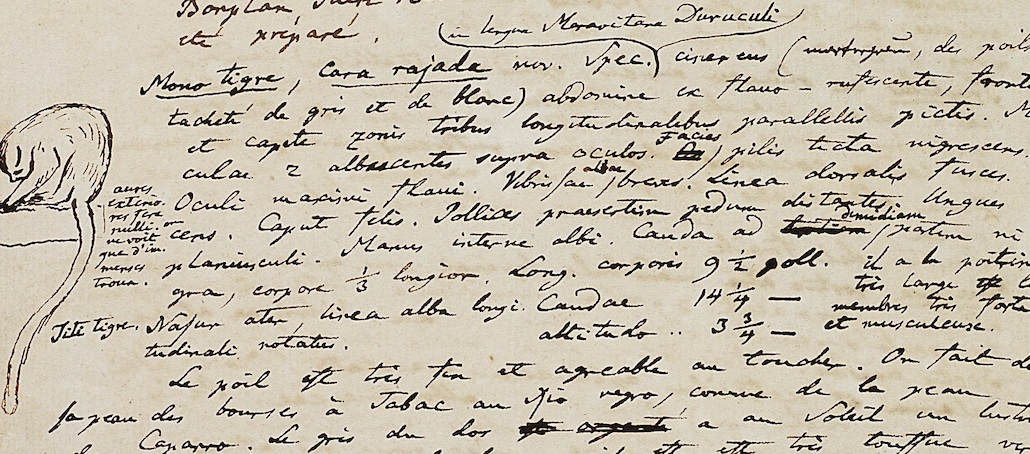

A detail from Humboldt’s South American tagebücher. He started the 4,000-page journal in German and later switched to French, with margin notes in Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Latin, Greek and English. Staatsbibliothek Berlin

Of all Humboldt’s contributions to the sciences, perhaps the most significant was his ability to see diverse disciplines as part of a whole. Describing the disastrous effects of clearcutting and monoculture in colonial plantations in Venezuela in 1800, Humboldt became the first scientist to write about the potential for human-induced climate change. “Humboldt was the first to explain the forest’s ability to enrich the atmosphere with moisture and its cooling effect, as well as its importance for water retention and protection against soil erosion,” Andrea Wulf wrote in the Atlantic. “When nature is perceived as a web, its vulnerability also becomes obvious. Everything hangs together. If one thread is pulled, the whole tapestry might unravel.”

Though best known for his journeys in South America, Humboldt continued his scientific explorations throughout his life. In 1829, at the age of 60, he embarked on a 10,000-mile expedition to the far corners of Russia, and returned as restless as ever. “I have seen much, but, measured by my demands, only very little,” he reflected the day before his 75th birthday. He continued to write and publish until a few weeks before his death in Berlin on May 6, 1859. He was 89.

On the centennial of his birth, September 14, 1869, The New York Times devoted the entire front page to the celebration of his life, and thousands gathered for the unveiling of his bust in Central Park. Though his notoriety has since faded, his name endures. More than 100 animals, 300 plant species, and an asteroid are named in his honor, not to mention mountain ranges, universities and 13 towns in North America alone. His legacy remains in all of us that consider the health of the environment inherently connected to our own wellness and survival as a species.

Words by Matt Hart with a September, 2022 update by Jeff Moag.