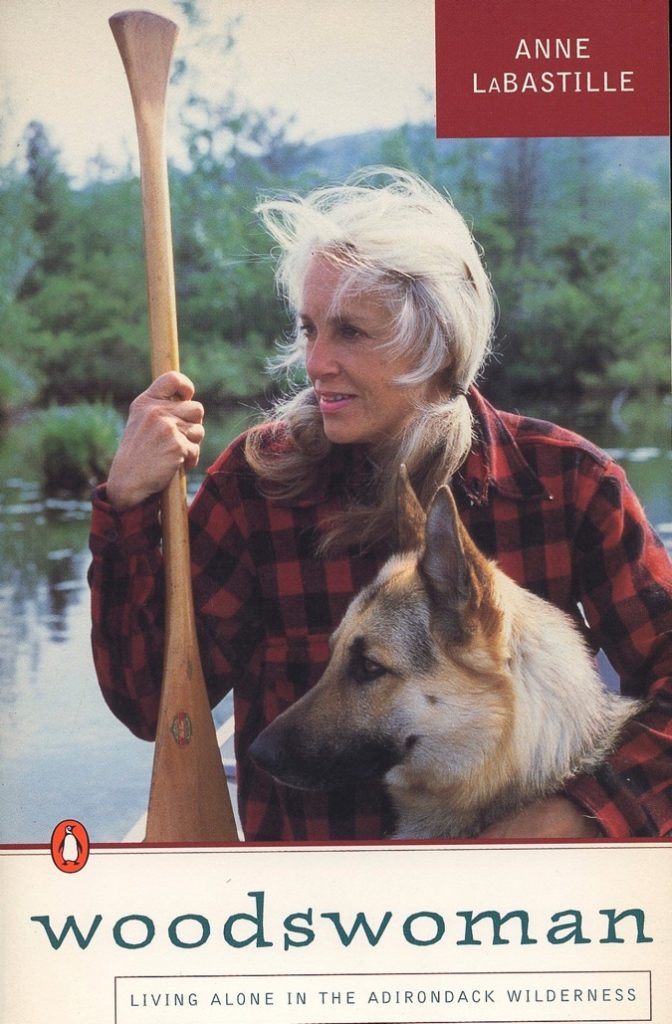

Few memoirs are as aptly titled as Anne LaBastille’s Woodswoman.

Published in 1976, the book is the first in a four-volume autobiographical series written by LaBastille, an ecologist, environmentalist, recluse, author, and professor, among many other titles. Could just as easily add woodworker, builder, philosopher, guide, and teacher to that list. LaBastille’s books chronicle her life living alone—well, not entirely alone, she was never far from her beloved German Shepherds—in a log cabin she’d built herself in the Adirondacks. A female Henry David Thoreau. She actually modeled her cabin after Thoreau’s Walden Pond cottage, as a matter of fact.

Woodswoman was perfectly timed upon its release to capture the energy of two cultural waves sweeping the nation—feminism and the environmental movement. Just a year earlier, the UN declared 1975 The International Year of the Woman, and Time Magazine’s Man of the Year Award went to “American Women.” Gloria Steinem battled with Phillis Shlafly over the Equal Rights Amendment.

At the same time, Congress busied itself with passing laws like the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, and the Endangered Species Act, among others.

And in this environment, LaBastille was tapping into both movements, having carved out her own world as a nature writer, inspiring women to seek adventure in the backcountry, to engage with the wilderness on their own terms.

“Those books were really important for a large cohort of women interested in conservation and the outdoors — hiking, guiding, fishing — all things that Anne did,” said James Lassoie, a professor of international conservation at Cornell University who worked with LaBastille.

LaBastille was born in New Jersey in 1933, but went to school at Cornell, in Upstate New York, where she received a bachelor’s degree in conservation. A few years later, she took a master’s in wildlife management from Colorado State University. Part of her graduate work involved LaBastille tromping around Guatemala, where, near Lake Atitlan, she’d become fascinated by a giant, flightless bird called the “Poc” by locals. LaBastille made the bird and efforts to save it the subject of her doctoral dissertation at Cornell, where she earned her PhD in 1969.

By then, LaBastille had already moved deep into the Adirondacks. She’d been married for a time, but when the relationship petered out, LaBastille took refuge in the wilderness. She built her small log cabin in 1965 on the shores of Twitchell Lake. LaBastille lived there with no electricity and no plumbing. It was 12 feet by 12 feet, and it contained everything LaBastille needed; a small stove and a typewriter, the latter she used to write her way into America’s backcountry heart.

The Adirondacks were her muse. When she wasn’t writing, LaBastille gave tours into the heart of the mountains, working as a canoeing and backpacking guide. But mostly, she wrote and wrote and wrote. 16 books. Over two dozen scholarly articles, many of which focused on environmental challenges facing her beloved Adirondacks. LaBastille was a prolific freelance writer for magazines like Backpacker and National Geographic. She walked through the forest, sat quietly observing the lake, and wrote some of the most beautiful prose about nature.

“Sometimes I sit in my log cabin as in a cocoon,” she once wrote, “sheltered by swaying spruces from the outside world. From traffic, and noise, and liquor, and triangles, and pollution. Life seems to have no beginning and no ending. Only the steady expansion of trunk and root, the slow pileup of duff and debris, the lap of water before it becomes ice, the patter of raindrops before they turn to snowflakes. Then the chirp of a swallow winging over the lake reminds me that there is always a new beginning.”

When Woodswoman came out, LaBastille was showered with fan letters. She’d called her lake “Black Bear Lake” to keep its identity hidden, but readers combed the Adirondacks looking for her cabin and sent volumes of mail to her publisher which arrived in stacks at the foot her humble lakeside writer’s studio. Many men who’d read her work became enthralled with a blonde Daisy Duke-wearing, tough-as-nails mountain woman living a rustic writer’s life in a cabin, and would seek her out at the lake, bearing gifts, occasionally marriage proposals.

LaBastille drew crowds in the hundreds for book signings in Upstate and for talks about ecology and the history of the Adirondacks.

“It’s hardly an exaggeration to call Anne the Carl Sagan of conservation,” said Lassoie. “To many, she embodied the Adirondacks because she was able to communicate a feeling of concern and ownership to countless readers worldwide.”

LaBastille so revered the Adirondacks she became a charter member of New York State Outdoor Guides Association and was commissioner of the Adirondack Park Agency for nearly two decades. All of this as a woman in an outdoor industry still very much dominated by men.

Her role as commissioner of the APA had ramifications for decades. LaBastille helped incorporate science and ecology into nearly all decision-making aspects of the park. She also railed against threats to the natural environment there, often earning the scorn of sportsmen and private landowners unaccustomed to being told, especially by a woman, what they couldn’t do on their property.

Eventually, she bought property near Lake Champlain, leaving her writing cabin behind. So beloved is LaBastille in Upstate, however, the cabin was relocated to the Adirondack Experience Museum on Blue Mountain Lake. There, LaBastille’s fans can stand for a spell and imagine her clacking away on a typewriter, praising the natural world around her, warning of increasing threats to a place she dearly loved, while reaching down to give her dogs a scratch.

Photo: Anne LaBastille collection