Quickly after Andrew McAuley disappeared simply 30 miles from the tip of a 1,000-mile kayak crossing from Tasmania to New Zealand a dozen years in the past, pundits started second-guessing him. Nothing might be price such threat, they scolded, particularly to a person blessed with a loving spouse and younger son.

McCauley, whose resumé included paddling 330 miles throughout Australia’s Gulf of Carpentaria and three kayak crossings from Australia to Tasmania, had deliberate meticulously for the journey, putting nice belief in a selfmade cockpit cover designed to proper his modified manufacturing kayak within the occasion of a capsize. The cover, nicknamed Casper, did that job on a number of events, however McCauley’s video diary, discovered when the kayak was recovered with out the cover, tells of him having to climb again into the kayak after being ejected in a tough capsize. The video additionally reveals that McCauley had glimpsed the excessive mountains of New Zealand’s South Island within the final hours of his life. He’d come that near finishing one in all historical past’s most audacious ocean crossings.

“Evidently in case you stay, then by definition you’re a competent, risk-taking explorer. However in case you die, it’s too straightforward to name you a loopy suicidal,”

If he had managed one other 30 miles we’d have hailed him as a genius, kayak adventurer John Turk advised me on the time. “Evidently in case you stay, then by definition you’re a competent, risk-taking explorer. However in case you die, it’s too straightforward to name you a loopy suicidal,” he stated.

McCauley by all accounts was a prudent adventurer, although additionally a pushed one. He began as a rock climber and mountaineer, placing up dozens of big-wall routes in Australia and alpine first ascents in New Zealand, Patagonia and the Himalayas within the 1990s. He took little curiosity within the marquee peaks, preferring to check himself on lesser-known however extra advanced routes, such because the south ridge of Ama Dablam (6,854 meters) in Nepal and the primary ascent of Mt. Jo, a rocky spire reaching 5,400 meters in Pakistan’s Nangma Valley.

Nearer to residence, McAuley and Vera Wong pioneered a line referred to as Evolution in Bugonia Gorge. The route was a favourite of McAuley’s, and a fall there in 1998 launched his kayaking profession, albeit not directly. McAuley plummeted 30 meters when a handhold pulled free, ripping two units of safety from the rock and smashing his knee towards the cliff. The impression shattered his patella, and he by no means absolutely recovered.

Earlier that 12 months McAuley and his spouse Vicki introduced kayaks to Patagonia to entry the Dedos del Diablo, a set of un-climbed spires on the sting of Chile’s promisingly named Fiordo de los Montañas. After his accident, McAuley took a better curiosity in sea kayaking. The knee harm meant that within the mountains, McAuley would attain his bodily restrict effectively earlier than his psychological one. Within the kayak, there was no such limitation.

“I’ve all the time been drawn to challenges on the sharp finish of what’s attainable, initially with climbing and mountaineering, and extra just lately with sea kayaking,” McAuley wrote earlier than his 2007 Tasman try. He deliberate to publish a e-book when he completed the crossing and had, in reality, already written a great deal of it. His spouse Vicki included a few of his writings into her 2010 e-book about McAuley and his crossing, Solo.

“Ant had all the time stated a well-built kayak is restricted not by the modest dimensions of the craft, however by the creativeness and talent of the individual sitting within the cockpit,” she wrote. McAuley had no scarcity of creativeness, and his talent grew in line with his more and more formidable kayaking missions.

McCauley’s rig, left, with McCauley and Casper, proper. Photograph: Paddling Journal.

He crossed Bass Strait, the 140-mile physique of water between Tasmania and the Australian mainland 3 times by kayak, first by island-hopping alongside the japanese fringe of the strait, then on the west with one cease, and at last a nonstop crossing. Borrowing a climbing time period, McAuley referred to as the 36-hour epic his “Bass Strait super-direct.” Towards the tip he fell asleep, capsized, and rolled up with out lacking a beat. Later, nonetheless miles from the end, he referred to as Vicki from the kayak and advised her he’d arrived safely ashore. She was pregnant with their son, Finlay, and he didn’t need to fear her.

When he received residence from the super-direct, he pulled out the Instances Atlas of the World and a tape measure, Vicki writes in Solo.

“Take a look at this,” he beckoned. “The Gulf of Carpentaria. It’s solely 5 centimeters on the map.”

In life, the good bay on Australia’s north coast is 330 miles throughout. McAuley spent almost every week paddling throughout it in 2004, sleeping at sea in his sea kayak.

After that, the Tasman Sea was all that was left.

McAuley balanced fatherhood, coaching and work by commuting in his kayak throughout Sydney harbor to his job as an IT marketing consultant. He estimated the 1,000-mile Tasman crossing would take a month, give or take. For a visit of that size in that a part of the world, there’s no such factor as a climate window. His route from Tasmania to New Zealand’s South Island put him within the Roaring 40s, on the sting of the nastiest ocean on the earth.

Within the years earlier than and since McAuley’s disappearance, kayakers have notched an ever-longer record of inconceivable ocean crossings, to not point out a list of harrowing shut escapes. Aleksander Doba was 70 throughout his third Atlantic kayak crossing in 2017. However his boat resembles a survival capsule as a lot as a kayak, with an enclosed cabin and elaborate self-righting mechanism. Justin Jones and James Castrission used the same craft for the primary kayak crossing of the Tasman in 2008, as did Scott Donaldson, who made the one profitable solo kayak crossing in 2018.

McAuley proposed to paddle the Tasman in a manufacturing sea kayak.

The one factor remotely comparable was Ed Gillet’s 1987 crossing from Monterey, California to Hawaii in a calmly modified double kayak. Rightly heralded as the best sea kayak voyage of all time, Gillet’s crossing was additionally a succession of narrowly averted disasters. Out of meals and hallucinating after 2,200 miles and 63 days at sea, he almost missed the islands altogether.

McAuley’s route could be shorter, however the climate was doubtlessly far worse. The largest problem, other than the bounds of psychological and bodily endurance, could be trip out the inevitable storms he would encounter alongside the best way. McAuley’s reply was Casper, a fiberglass cowl he deliberate to lock over the cockpit of his 19-foot Mirage sea kayak at night time and in unhealthy climate. It regarded like an inverted trash can with an enormous smiley face painted on it.

McAuley advised me about Casper the one time we spoke, in December, 2006. I used to be searching tales and caught wind of his, so I picked up the cellphone and we talked for an hour, by no means thoughts the worldwide charges. I used to be working late on a winter Friday in Colorado, he was having fun with a summer season Saturday morning in Australia. Nonetheless, we related. We’re the identical age and had each spent our lives chasing journey—me with a digital camera and notepad writing trendy myths within the third individual, him on the market, dwelling them.

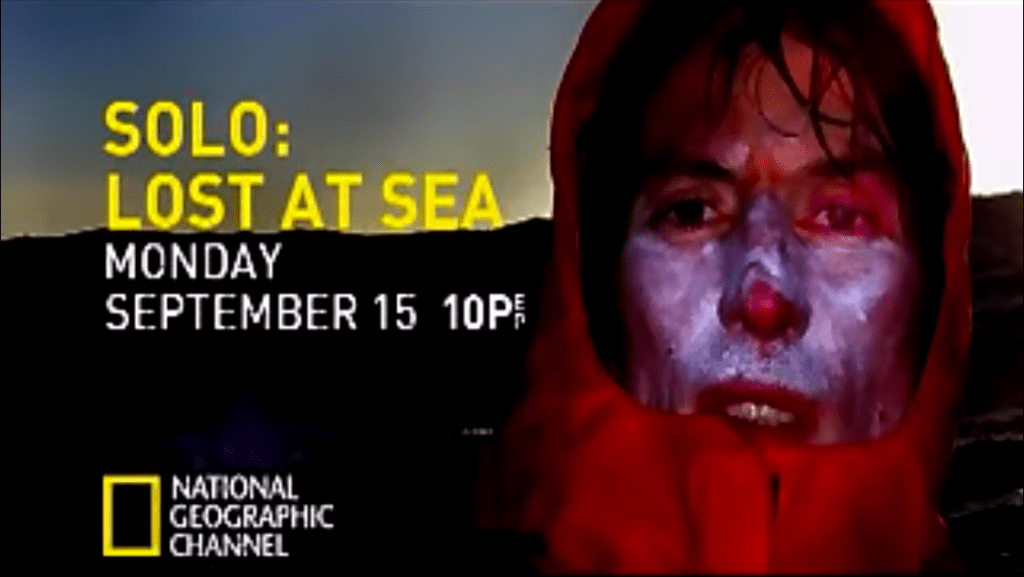

The award-winning 2008 documentary Solo: Misplaced at Sea documented McAuley’s harrowing crossing.

I requested the standard goading questions, searching for one thing to hype. Do you are worried in regards to the hazard? I requested, or the excessive winds, the chilly seas, being alone? And that’s when he advised me about Casper. He would clamp that fiberglass emoticon over his cockpit and belief it to maintain him upright and dry, 500 miles from the closest land. When he advised me he’d constructed it “out within the again shed,” I believed there’s a quote I can construct a narrative on. So Australian. So completely telling of his method.

I advised my editors his was the kayaking story of the 12 months, all the time slipping within the caveat, “if he makes it.” By which I meant if he didn’t stop. I ought to have identified higher.

The heavy climate got here in earnest when McAuley was about two-thirds of the best way throughout the Tasman, bringing 30-foot seas and 40-knot winds. He had determined prematurely to not request assist in such circumstances. Locked within the kayak beneath his smiling yellow dome, McAuley had in his hand a beacon that will mechanically set off a rescue. He didn’t use it.

“Andrew spent 28 hours locked up in his kayak with the beacon proper there,” his weather-router Jonathan Borgais advised The Age. “He would have rolled a number of occasions. He had the nerve all that point to not activate the beacon, however saved sending me messages.” One learn, “No picnic right now.”

Twelve days later, with simply 80 miles to go to Milford Sound on New Zealand’s South Island, he messaged Vicki: “See you 9 a.m. Sunday!” It was Thursday. The climate forecast promised a quiet finish to a harrowing journey. Vicki was already ready in Milford Sound with Finlay and a cadre of well-wishers, together with the legendary Kiwi kayaker Paul Caffyn who deliberate to paddle out and meet McAuley with ginger beer and a bottle of whiskey.

The subsequent night, the New Zealand Coast Guard obtained a garbled misery name. It was McAuley, reporting that his kayak was sinking, 30 miles from Milford Sound. Within the recording, his voice is nearly unintelligible. He sounds deeply fatigued, or maybe hypothermic. Some thought the message a hoax. A small search was launched that night time and expanded the next day. The kayak was recovered about 24 hours after McAuley’s final transmission. It was lacking solely the cockpit cover. The paddle, satellite tv for pc cellphone, GPS, and beacon—nonetheless not not activated—had been all in working order contained in the kayak. McAuley was by no means discovered.

Nobody is aware of what occurred in his final hours. The prevailing concept is that kayak capsized and McAuley grew to become separated from it. With Casper stowed on the rear deck, the boat was inconceivable to roll, and climbing again in was a sketchy prospect in the very best of circumstances. McAuley had carried out the maneuver twice throughout his crossing, and reported it had been ‘gnarly’ each occasions. In his fatigue it’s attainable he couldn’t get again within the boat. Or it could have merely slipped from his grasp. Even in mild winds, a kayak will drift sooner than a person can swim.

Within the days after McAuley’s demise, of his boat made the rounds. Taped in entrance of the cockpit was a snapshot of McAuley’s son. The picture took me again to the dialog we’d had a few months earlier than, and the way I’d been so taken with McAuley’s can-do angle. Even his motivation was improvised, I believed: that photograph of Three-year-old Finlay caught to the entrance deck of his kayak. One thing to maintain him going by the capsizes, the 30-foot seas and the 40-knot gales and, I can’t cease myself from considering, the very last thing he noticed because the kayak slipped away. How lengthy did he swim in that chilly, empty sea, understanding that lovely baby was ready on the opposite facet?