To those with restless, wandering souls, the promise of a frontier, a hazy zone marking the edge of the known and what lies over the horizon, is an irresistible force promising adventure, the slaking of an endless thirst for discovery. Through much of the early 20th century in the US, the frontier was Alaska, the last bit of North America left to be tamed. For wanderers, Alaska meant soaring mountains, cascading rivers, great stands of spruce, salmon tail-walking across estuaries, and bears the size of buses grumbling through the bush. For developers, Alaska meant new opportunities for industry, and plentiful natural resources to be exploited.

Celia Hunter, a pilot and adventurer turned conservationist, said to hell with that.

She, along with close friend Ginny Wood, stood athwart the line separating the Alaskan frontier from the long-settled US with a firm hand raised against the industrialists who salivated over the endless possibilities of plunder that a territory of Alaska’s size promised. For half a century she helped keep the dams, the bulldozers, even, unbelievably, atomic bomb detonations from marring one of the world’s wildest places.

Still, a young Hunter would have been surprised to learn that one day she’d be one of America’s greatest conservationists.

Hunter was born in 1919, in Arlington, Washington, a small town then and still today, in the western foothills of the Cascades, an hour’s drive north of Seattle. She was raised as a Quaker, living and toiling modestly on her family’s farm during the Great Depression.

But in 1941, just before war came to the US, Hunter abruptly broke with Quaker tradition and trained to fly airplanes as part of the Civilian Pilot Training Program. Despite the “civilian” part of the name, the program was designed to provide the military with a pool of qualified pilots. It’s unclear why a Quaker like Hunter would decide to learn to fly in a program very much on the Army’s foyer, though as she showed throughout the rest of her life, sitting idle was unbearable. Perhaps flying, regardless of what she was flying, represented the easiest avenue for excitement.

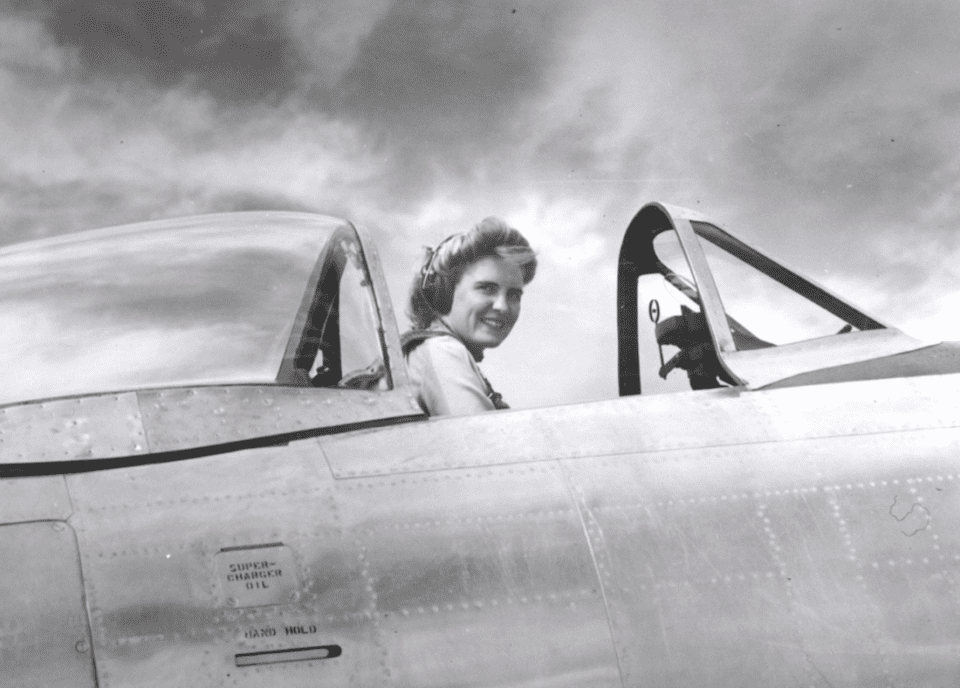

In 1943 Hunter, having earned her pilot’s license, joined the Women Air Force Service Pilots (WASP) program, where she learned to fly cutting-edge fighter planes, like P-51 Mustangs and P-47 Thunderbolts, among other military aircraft. The WASPs ferried the planes around the country from factory to airbase. While a WASP, Hunter made a lifelong friend and business partner when she met fellow WASPer Ginny Wood. The two had tired of flying back and forth across the middle of the country, and longed to fly the routes considered too dangerous for women pilots—those that crossed north Canada and entered the Arctic airspace of Alaska.

Their solution was the private sector.

In December 1947, Hunter and Wood (how great do those names sound together?) arranged a deal to fly two planes from Seattle to Alaska, to deliver the aircraft to their new owner in Fairbanks. The flight was scheduled to take 30 hours with refueling and rest stops. It took 27 days because the weather was so awful. When they finally arrived in Fairbanks, the temperature was minus 50 degrees Fahrenheit.

For half a century she helped keep the dams, the bulldozers, even, unbelievably, atomic bomb detonations from marring one of the world’s wildest places.

“Ginny’s plane had unairworthy fabric and no heat—we nicknamed it ‘Lil’l Igloo,’” Hunter said, later. “On the leg between Watson Lake and Whitehorse, a three-hour flight, we had to chip her out of the cockpit when we landed; she was so cold she couldn’t move!”

They were hooked.

“I don’t think ‘conservationist’ existed in my vocabulary at that time,” Hunter once remarked. “We were just looking for adventures!”

Through the first winter and into the summer, Hunter and Wood worked flying early Alaskan tourists into Nome and Kotzebue. When summer turned to fall, wanderlust returned, and the women headed off to a university program in Sweden. While there, they bike toured through a devastated Europe only a few years removed from total war. Missing the expanses and wilderness of the US, they returned home, hitching a ride on a tanker steaming across the Atlantic.

Once back in Alaska, Hunter and Wood decided to replicate one of their favorite things they encountered on their European voyage—the alpine hut system.

Wood had married a Denali National Park ranger (though Alaska was not yet a state, the national park was already in existence) and along with her husband, joined Hunter in purchasing a piece of land with an expansive view of Denali’s namesake mountain. In 1952 they opened Camp Denali, a modestly appointed backcountry refuge. “Although the term had not yet been invented, Camp Denali was probably the first eco-tourism venture in Alaska, possibly the U.S.,” Hunter said.

Hunter and Wood operated Camp Denali until the mid-70s, when Hunter turned her considerable focus solely to protecting Alaska’s wilderness.

She’d been involved in conservation for 20 years by that point.

In 1960, Hunter was a founder of the Alaskan Conservation Society. The group was organized to marshall public support for the newly proposed Alaskan National Wildlife Range (what would later be renamed the Alaskan National Wildlife Refuge). Congressional support for ANWR existed entirely outside of the Alaska delegation when the Arctic range was first proposed in 1956. Outside groups saw the benefit of protecting huge swaths of wilderness from resource exploitation and development, but Alaska’s own representatives resented outsiders telling them what to do; they also viewed Alaska’s resources as a huge financial windfall.

Hunter enjoyed Alaska in every possible medium. Photo: Connie Barlow

The ACS was a way to encourage Alaskans to voice support for wilderness, to speak louder than the industrial interests who wanted open ranges for resource extraction. Those voices made it clear to the White House, where just before leaving office in 1960, President Eisenhower granted federal protection to ANWR.

Her primary battle won, Hunter went on to serve as Executive Secretary of ACS for the next decade. She spurred the organization to a battle against a massive dam on the Yukon River that would have flooded hundreds of miles of wilderness. She led the ACS in a victory against Project Chariot, a plan almost too crazy to be true, that would have seen the Atomic Energy Commission oversee the detonation of four nuclear warheads to create a deepwater harbor along the northwest coast.

In 1980, the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, passed a fight that took had ongoing for a decade and that Hunter was heavily involved in. ANILCA set aside more than 50 million acres of Alaska to be protected as federal wilderness areas.

Realizing what the conservation movement had bitten off, Hunter went on to help create the Alaska Conservation Foundation to raise money to help fight against the interests who she rightly understood would continue to fight to open Alaska to drilling and mining.

Hunter never stopped exploring the place she loved either. She continued to fly planes over the Alaskan bush, something she’d dreamt about decades before as a WASP. Hunter hiked, kayaked, camped, and marveled at the immense natural beauty around Camp Denali. She gave speeches and radio interviews praising fellow conservationists while arguing tirelessly for the preservation of natural spaces.

On December 1, 2001, Hunter spent a day cross-country skiing near her Fairbanks home. She then settled in for an evening writing letters and sending faxes to Congress in support of conservation causes. Hunter died peacefully in her sleep at home.

Wood, who outlived her close friend by a decade, remarked after Hunter’s passing:

“At 82, she had slowed down but not in her zest for life, or involvement in issues. What a loss. What a graceful exit of a well-lived and long life.”

Will Curtis, the late and beloved Vermont Public Radio host interviewed Hunter just days before she passed. She spoke to Curtis about what being a conservationist meant, that it required real work and sacrifice to protect the places we love.

“I want to leave with you the idea that change is possible,” Hunter said. “But you’re going to have to put your energy into it.

Top photo: Connie Barlow

You’re probably wanting to read more about Celia Hunter, and we don’t blame you. Start with Women Pilots of Alaska: 37 Interviews and Profiles, available used, here.

For more about visionary conservationists behind the creation of ANWR, check out Two in the Far North, by Margaret Murie. Her husband was Olaus Murie, famed biologist, who helped map the original ANWR. Margaret went on to found the Wilderness Society, for good measure.

Source: advanture-journal

2 comments

F*ckin’ awesome things here. I am very glad to see your post. Thanks a lot and i’m looking forward to contact you. Will you please drop me a mail?

You are my aspiration, I own few blogs and rarely run out from to post .