It was a simple mission: Travel farther north than anybody else ever had. In 1881, the record for reaching “Farthest North” was held by the British. America wanted it. So, the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition was launched. The men, led by Lt. A. W. Greely, succeeded in claiming their prize of Farthest North, but then their resupply ship never came. They hunkered in camp for two frigid winters then, determined to live, began pushing south.

Their story is told in the new book, Labyrinth of Ice, by Buddy Levy. Below, is an excerpt.

***

July 9, 1881— Labrador Basin, North Atlantic Ocean

Lt. A. W. Greely, commander of the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition, rode at the bow of the two- hundred- foot- long steamship Proteus, his vision fixed on the northern horizon. He wore a double- breasted, boiled-wool peacoat with thick fur at the collar and cuffs. He and his crew were bound for the top of the world, to one of the last regions yet unmarked on global maps. As the inlet narrowed near the strait of Belle Isle, they passed great protruding shapes of ice rising from the sea. Some resembled immense white- blue anvils, and some looked like the wind- scoured sandstone towers he’d seen in the American Southwest. Most of the icebergs he could not describe, or compare to phenomena he had ever witnessed before in nature. He observed them and everything else, squinting through his oval spectacles at the breathtaking expanse, trying to visualize what lay ahead. The combination of ice, rock, and water appeared to have some vague kind of course he might plot his way through. As the Proteus plowed into the wind-chopped Labrador Sea, massive slabs of glacial ice cleaved off the shore and crashed into the sea, spewing freezing brine over the gunwales and frosting his sharp narrow face and pointed black beard.

His heart raced with anticipation, but his mind was much burdened. Less than a week earlier, on July 2, at the Baltimore and Potomac Rail Station in Washington, D.C., President James A. Garfield had been shot twice at pointblank range—once in the shoulder and once in the back, the second shot lodging near his pancreas—and now, with family and physicians huddled around him, he fought for his life at the White House. Greely’s heart was heavy at this news, with the uncertainty of how another presidential assassination—should Garfield not recover—would rock the Republic. And he already missed his young family, his wife of just three years, Henrietta, and their two infant daughters, Antoinette and Adola. But the call of adventure—and possibly international fame—had lured him toward the Arctic on a voyage of exploration and discovery that would last at least two years, should all go as planned. However, Greely was savvy enough to know that Arctic journeys never went as planned. He had spent years studying the history of Arctic exploration and the quest for the Northwest Passage, and he understood the dangers and stark realities: He steered toward a harsh, ice-bound labyrinth where crew losses of 50 percent or more were the norm. But Greely had some hard bark on him, a war-earned toughness coupled with an uncanny sense of the thing to do now, and he hoped his men had it too. They’d better: A. W. Greely would allow no disorder. This was sovereign. He’d started following orders when he was seventeen, then nicknamed “Dolph” by his friends. He’d been weaned on discipline. Now he was the one giving the orders, and he demanded a strict, unwavering adherence to them, and to discipline generally.

Poor weather and northwesterly gales slammed into the Proteus, slowing progress, but within a week they’d steamed into the Davis Strait, where they encountered their first pack ice.

Greely was fascinated and awed by the ice, noting in his journal that

the greater part of the ice ranged from three to five feet above the water, and was deeply grooved at the water’s edge, evidently by the action of the waves. Above and below the surface of the sea projected long tongue-like edges. . . . The most delicate tints of blue mingled quickly and indistinguishably into those of rare light green, to be succeeded later as the water receded from the floe’s side by shades of blueish white.

They passed more bergs, some jutting fifteen feet from the water, the ice rising in giant hummocks and pinnacles. Greely contemplated the threefold mission at hand: First, he was to set up the northernmost of a chain of a dozen research stations around the Arctic, to simultaneously collect magnetic, astronomical, and meteorological data. This was part of a revolutionary scientific mission named the International Polar Year (two years, really)—a global effort to record data at the farthest reaches of the world to better understand the earth’s climate. Second, Greely would search for and hopefully rescue the men of the lost USS Jeannette, which had vanished two years earlier during an attempted voyage to the North Pole. Greely had known Lt. Cdr. George W. De Long, the expedition’s leader, very well. He would try his best to find him. Third—though definitely not last—Greely secretly intended to reach the North Pole; or, should he fall short, to attain Farthest North, an explorer’s holy grail of the highest northern latitude, which had been held by the British for three hundred years.

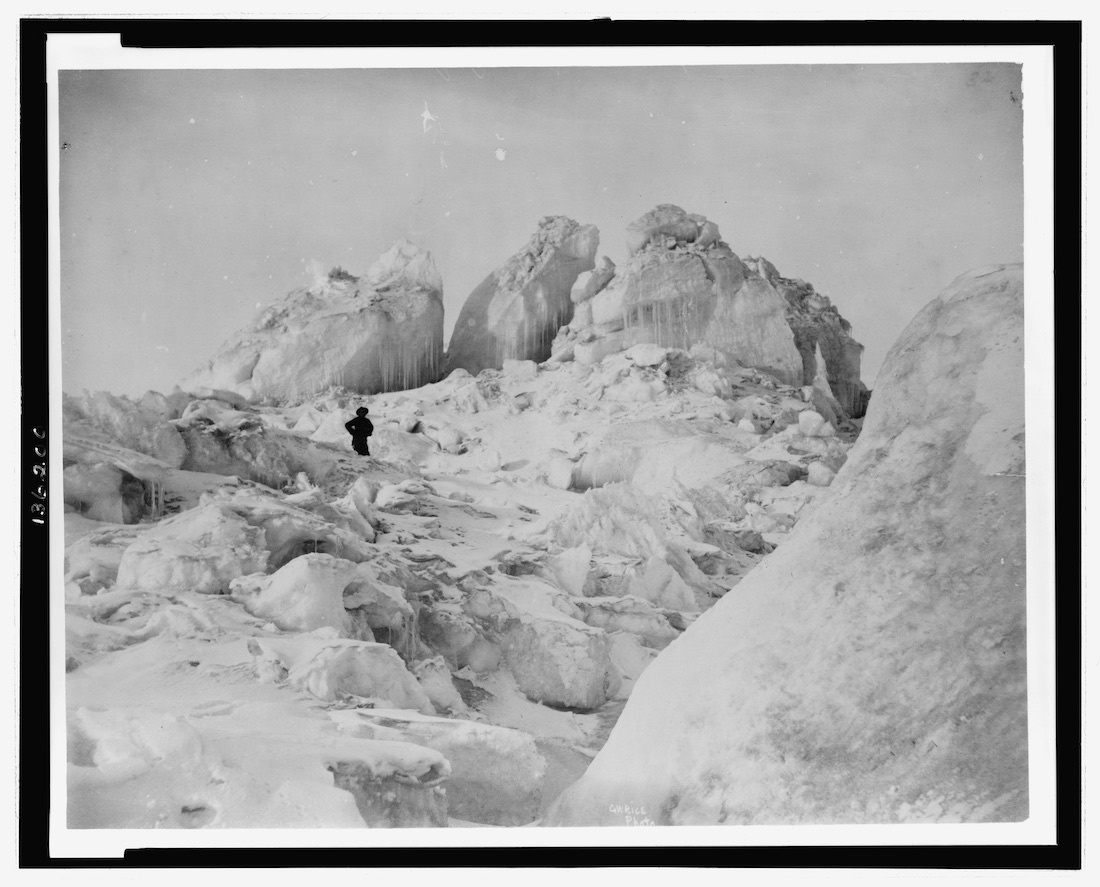

Hospital Steward Biederbick at the Dangerous Ice Foot near Fort Conger.

Credit: Library of Congress.

The Proteus—christened and launched new in 1874 out of Dundee, Scotland—was a 467-ton, iron-prowed steamer designed for the sealing trade. It was built to last a half century or longer if well maintained. The ship was commanded by Capt. Richard Pike, one of the most experienced ice navigators in Newfoundland. Pike coursed northward with unusual speed for the season, clipping through the normally ice-choked waters of the Davis Strait. Cutting through dense fog and wave chop, the sturdy steamship made land at the windswept western shores of Greenland at Godhavn (now Qeqertarsuaq), Disko Island. Through lifting fog, Greely and his men saw mountains rising up from the sea some three thousand feet, and along a secure, landlocked harbor and tranquil cove sat a native settlement under Danish control.

They remained in Godhavn for five days. There was also expedition business to attend to. Greely purchased a team of twelve Greenlandic sled dogs, the pack snarling and vicious. He would need these animals, as well as Greenlandic sled drivers he still had to enlist, for his intended sorties toward the North Pole. Greely also bartered for a large quantity of mattak—the skin of the white whale—which he’d learned from reading previous expedition logs was “antiscorbutic”—important in helping to prevent scurvy.

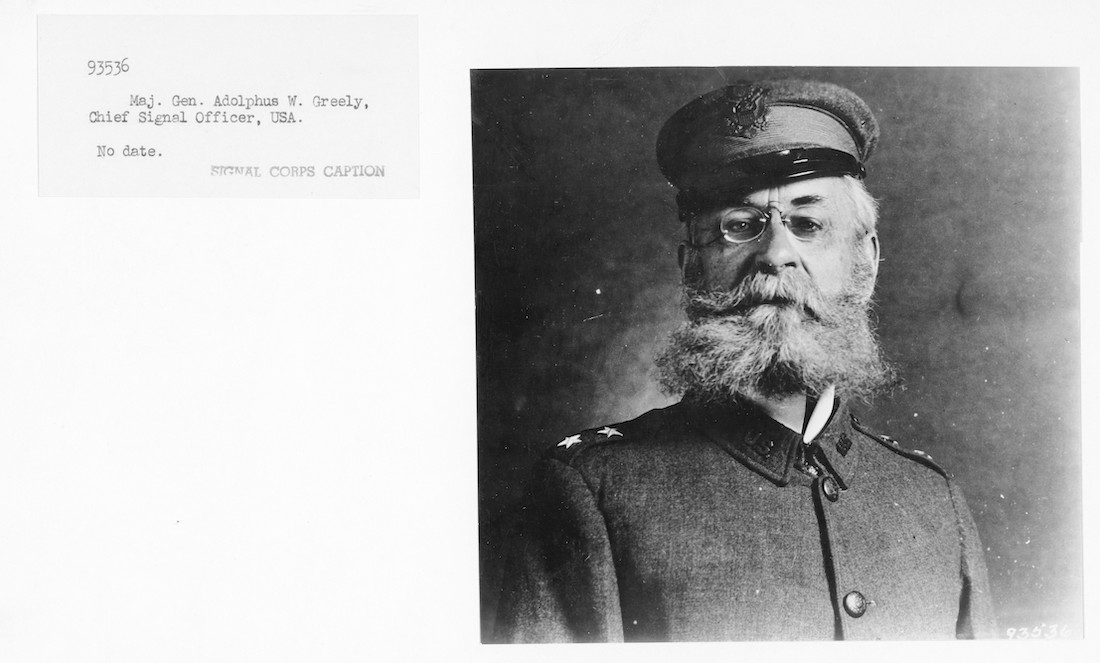

Greely as Chief Signal Corps Officer

Credit: Naval Heritage and History Command

Thus provisioned, Greely ordered Captain Pike to steam the Proteus ahead toward the dreaded Melville Bay, a three-hundred-mile-wide body of turbulent water known as a “mysterious region of terror.” The bay’s churning, swirling currents were much feared by whalers, and Greely had read that in one season alone, nineteen ships were lost there, some blown off course and capsized in the howling, freezing gales, others crushed and splintered between massive bergs. They plowed through thin “pancake ice” barely an inch thick and marveled at the massive floating icebergs gleaming white and blue-green in the perpetual sunlight. But that year, one of the fairest summers in memory, the waters of Melville Bay remained remarkably open, and on July 31, lookouts sighted Cape York. Captain Pike had navigated the watery graveyard in an unheard-of thirty-six hours, the fastest crossing then on record. Greely was pleased with the speed, but he privately wondered whether such open waters were an anomaly. What if the sound was not as open when the ship to relieve him attempted to pass through?

From LABYRINTH OF ICE by Buddy Levy. Copyright © 2019 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.