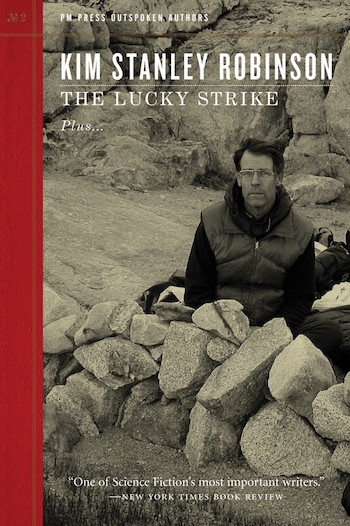

Backpacking can teach one many things. Persistence. Planning. Decision making. Confidence. Stoicism. And of course, a deeper awareness and appreciation of our home planet. For writer Kim Stanley Robinson, a celebrated sci-fi novelist, forays into the High Sierra have resulted in a lifetime of writing novels about humanity’s future in a climate change-ravaged world, in which humans gather strength from the qualities Robinson has learned deep and high in the mountains.

His books focus on the Earth’s people finally getting their shit together after climate change becomes (even more) destructive and threatening. Scientists and government officials become kinds of heroes for making brilliant decisions necessary to preserve life, fanciful experiments to settle Mars and other extraterrestrial planets and moons are revealed as impossible, and a new kind of awareness that our future is, of course, on *this* planet, not some other Hail Mary biosphere. We must work with what we have, Robinson would say, but also, hey, what we have is worth saving.

His most recent book, The Ministry For the Future, published in 2020, has been a huge hit among people who either are, or write about policymakers, as it outlines a near future world in which capitalism is tamed, carbon emissions have been curtailed, and humanity begins to enter a new, hopeful phase, despite horrific environmental calamity.

It also inspired a fantastic article in the current issue of The New Yorker, in which writer Joshua Rothman tags along with Robinson and a friend on a multi-day backpacking trip over a handful of high-altitude passes in the central Sierra. It’s a beautiful account of a novice hiker taking on a serious challenge and the joys that provides, while also showing that a love of nature can co-exist with a wary hope that technology provides a livable future for us all. Robinson has been described as a writer of non-fiction science fiction, fully aware of the challenges ahead of humanity, but with enough of his own hard-earned resilience to breathe life into a spark of hope.

Here’s a taste:

His most recent novel, “The Ministry for the Future,” published in October, 2020, during the second wave of the pandemic, centers on the work of a fictional U.N. agency charged with solving climate change. The book combines science, politics, and economics to present a credible best-case scenario for the next few decades. It’s simultaneously heartening and harrowing. By the end of the story, it’s 2053, and carbon levels in the atmosphere have begun to decline. Yet hundreds of millions of people have died or been displaced. Coastlines have been drowned and landscapes have burned. Economies have been disrupted, refugees have flooded the temperate latitudes, and ecoterrorists from stricken countries have launched campaigns of climate revenge. The controversial practice of geoengineering—including the spraying of chemicals into the atmosphere to reflect sunlight—has bought us time to decarbonize our way of life, and “carbon quantitative easing,” undertaken on a vast scale, has paid for the redesign of our infrastructure. But it’s all haphazard. We just barely escape the worst climate catastrophes, through grudging adjustments that we are forced to make. The rushed, necessary work of responding to the climate crisis defines and, for some, elevates, the twenty-first century.

And:

I was cold that night. The wind slipped under my tarp; my water bottle froze. In the morning, beside the jewel-like lake, I ate a protein bar and watched Robinson watch the sunrise. The sun’s progress was visible in the shadow that the mountains to the east of us threw over the mountains to the west. In “The High Sierra,” Robinson writes that the movement of such shadows reveals “the speed of the planet rolling under your feet.” The movement is “slow, but not so slow that you can’t see it. If you watch a boulder near the sun, but still in shadow, and keep watching it, then the sunlight will hit the top of the boulder, then move down the boulder—also the whole slope—slowly, slowly, but not imperceptibly, not quite.” He calls the sight “beautiful but disturbing”:

“This particular morning is passing at this very speed, it won’t come back. The rocks will be here for millions of years, but not this moment, which creeps down and down at you, even if you hold your breath, even if you suspend your usual busy stream of consciousness and just look at it, be with it. Time passes.”

I had read this description before the trip, but being there was different. I felt the world turn beneath me for myself. The ticking of the clock, the smallness of the Earth—more realizations.

You can read the entire story here, even without a New Yorker subscription. A link to many of his books, right here.