It was a bold plan, if not a very creative one.

Because she was a woman, Jeanne Baret was not permitted to sail on a French naval vessel. So the plan was she would dress as a man and present herself at the dock where Louis Antoine De Bougainville was preparing to embark on the first French circumnavigation of the globe. The voyage was the first by any nation to include a professional naturalist to catalog its discoveries, and that man, Philibert Commerson, would hire Baret on the spot as his assistant. Though they would pretend to be strangers, the two were intimately familiar. Commerson was Baret’s lover and employer, and according to at least one account, also her student.

They were an unlikely duo. Commerson was a well-to-do physician, a confidant of Voltaire who maintained a correspondence with the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus. She was an herb-woman, a peasant schooled in the traditional usage of plants, particularly medicinal ones. Though she was the daughter of poor day laborers and had no formal education, her knowledge of local flora was unsurpassed. According to Glynis Ridley’s 2010 biography “The Discovery of Jeanne Baret: A Story of Science, the High Seas, and the First Woman to Circumnavigate the Globe,” Commerson learned a great deal of practical botany from Baret, who was just 20 years old when they met in 1760.

Impressed with her botanical skills, he hired her as his housekeeper and assistant. They became lovers after Commerson’s wife died in childbirth in 1862. Baret was soon pregnant with his child, and moved with him to Paris where she gave up the boy for adoption, and the ambitious Commerson cultivated relationships with men of influence. Bougainville needed a chief naturalist for his world voyage, and Commerson got the job.

Commerson’s notes and collections added greatly to the science of botany, and all of that work was done in collaboration with Baret. Precisely how each contributed to the partnership is lost to history, but one thing is clear: Commerson accepted great risk to ensure that Baret travelled with him, and Baret took even greater chances to participate in the journey.

She bound her chest in linen, donned loose-fitting sailor’s clothes and presented herself at the gangplank using her father’s name, Jean. Commerson quickly signed young Jean aboard as his assistant and soon they were sailing west aboard the Étoile, a 111-foot cargo vessel with a crew of 116. Bougainville and another 214 men sailed on his flagship, La Boudeuse.

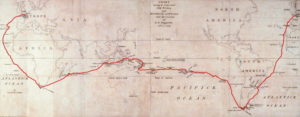

Bougainville’s circumnavigation, from 1766 to 1769. Baret spent five years in Mauritius, closing her circle in 1774. Wikimedia

Bougainville’s circumnavigation, from 1766 to 1769. Baret spent five years in Mauritius, closing her circle in 1774. Wikimedia

Secrets are hard to keep in such close quarters, though the task was somewhat easier because Commerson was given the captain’s cabin, in apparent deference to his status and the copious amount of equipment he brought with him for the collection and preservation of plant samples.

As his assistant, Baret shared those quarters, providing a safe haven and a place to use the toilet without blowing her cover. Still, it wasn’t long before sailors began to talk about the beardless young man who was never seen using the head. And when the other green hands stripped down for the ritual baptism at the equator, Jean was nowhere to be seen.

Eventually, the captain of the Étoile summoned Baret for an explanation, and he got a whopper. Young Jean confessed to having been captured by the Ottoman Turks, who according to French navy lore were in the habit of castrating their prisoners. This explained young Jean’s modesty around the other sailors, and the pitch of his voice. The captain chose to accept this fanciful tale, whether he believed it or not.

Baret spent most of her time at sea below decks, nursing the sickly Commerson. The 38-year-old botanist suffered an array of maladies, from severe seasickness to an ulcerated wound in his leg, the legacy of an encounter with an angry dog. When the expedition made its first landfall in Montevideo, Commerson explored as much as his leg would allow. Baret ranged farther, collecting hundreds of specimens.

At their next stop in Rio de Janiero, Commerson was unable to leave the ship. Rio was a dangerous place—the expedition’s surgeon was murdered there—but Baret went ashore anyway, collecting the most charismatic botanical specimen of the voyage, a colorful flowering vine Commerson called Bougainvillea, in honor of the expedition’s leader.

Their collection would eventually grow to more than 6,000 samples taken in South America, the South Pacific, New Guinea and the Indian Ocean. She carried the heavy wooden plant press, tools and an ever-growing load of samples—mostly plants, but also shells and even rocks—through the rugged terrain of Patagonia as the ailing Commerson did his best to keep pace. In his sporadic journal, Commerson marvels at Baret’s fortitude. Sticking doggedly to the male pronoun, he describes Jean admiringly as his “beast of burden.”

An artist’s interpretation of Bougainville’s arrival in Tahiti, where he received a surprise. Wikimedia commons.

The expedition was halfway around the world when Baret’s ruse was finally exposed, though exactly where and how is in some dispute. According to Bougainville’s published journals, she was unmasked in Tahiti when a group of islanders immediately recognized her as a woman, something her shipmates had only whispered about for 16 months.

Expedition’s surgeon François Vivès offers a similar explanation, writing in his journal that a Tahitian named Aotouru came aboard the Étoile and promptly remarked that Baret was a woman. Scholars now believe Aotouru described her using the Tahitian word for transvestite, noting matter-of-factly that cross-dressing was not merely a Tahitian custom, but apparently also a European one. In any event, the jig was up.

Some time later on the island of New Ireland in modern-day Papua New Guinea, a group of sailors confronted Baret and forced her to strip. This too is from Vivès, who describes the scene with a great deal of innuendo. While Baret gets only passing mention in three of the seven surviving journals of the voyage, Vivès spends a fair bit ink on her, motivated, perhaps, by a lingering feud with Commerson.

Ridley makes the New Ireland encounter the climactic scene of her biography, suggesting that Baret’s shipmates did not merely strip her, but also raped her. As evidence, she offers Vivès’ veiled account and the birth of her child about nine months later. We’ll never know for certain what happened on that beach 251 years ago. For Baret’s sake we can only hope that Ridley got it wrong, and according to Gerard Helferich’s review for the Wall Street Journal there’s a good chance she did.

“Throughout the book, actions, thoughts and moods of which no record survives are reported with authority. And so we’re privy to the ebb and flow of the lovers’ relationship, and we see Baret cowering in her hammock with a loaded pistol to protect herself from shipmates. Phrases such as ‘is tempting to imagine,’ ‘can be easily guessed at’ and ‘is not incredible to suppose’ appear often. And once such suppositions are planted, they have a habit of emerging later as demonstrated fact. Perhaps most troubling, there is no real evidence that the book’s horrifying climactic scene, involving rape, occurred at all.”

With Baret’s secret revealed, Bougainville had a powerful motive to put her ashore at his first opportunity. That chance came on the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius, then known as Isle de France. The island’s governor was a fellow botanist and old friend of Commerson named Pierre Poivre (later Anglicized and immortalized as Peter Piper of tongue-twister fame). Poivre insisted that Commerson stay on the island as his guest, likely with the encouragement of Bougainville. Baret, too, stayed on Mauritius, living with Commerson at Poivre’s estate. For a second time she gave up a child for adoption, and continued her botanical career in expeditions with Commerson to Madagascar in 1770 and Reunion Island in 1772.

Commerson died in 1773 at the age of 45, leaving Baret with a dilemma. He’d left her a modest inheritance, but she didn’t have the resources to return to France and claim it. She worked for a time in a tavern, married a soldier named Jean Dubernat and returned to France in late 1774 or early 1775.

More than eight years after starting leaving France dressed as a boy, she returned as the first woman ever to have sailed around the world. There was no fanfare, and it’s not clear whether Baret herself recognized the distinction. She was more intent on collecting the money Commerson left for her, which required a petition to the attorney general of France.

The significance of Baret’s circumnavigation was not lost on Bougainville, however, and much to her surprise Baret was awarded a state pension in 1785. The citation reads: “Jeanne Baret, by means of a disguise, circumnavigated the globe on one of the vessels commanded by Mssr. de Bougainville. . . . Her behavior was exemplary and Mssr. de Bougainville refers to it with all due credit.”

Commerson, too, remembered her in a genus of flowering shrubs, an example of which they found together on Madagascar. He named it Baretia bonafidia, but by the time the sample reached Europe years after his death the genus already had another name. Baret wouldn’t be immortalized in the taxonomy until 2012, when biologists Eric Tepe and Lynn Bohs named Solanum baretiae in her honor. It is a flowering vine found only in a mountainous zone in southern Ecuador and northern Peru known for its exceptional biodiversity.

1 comment

Thank you for the sensible critique. Me and my neighbor were just preparing to do a little research about this. We got a grab a book from our local library but I think I learned more from this post. I’m very glad to see such great info being shared freely out there.