We published a piece last year from Kang-Chun Cheng, a wildly talented photographer and writer who likes traveling to climbing areas that maybe aren’t at the front of mind for most. Her piece last time looked at some OG climbers in New Hampshire. This piece sees KC traveling through the southern Sinai Peninsula, contested terrain when it comes to global politics, less so when it comes to crags. We’re thrilled to be working with her again on this piece. – Ed.

Driving through the heady granite valleys––wadis, as they are called in Arabic––the terra-cotta coloured walls practically seem luminescent. We stare, astounded at the scale of Wadi Qnai’s beauty. If anything was going to freshen us up from a year, challenging both physically and emotionally, this would be it. Some classic rough-around-the-edges adventures in Dahab, on Egypt’s south Sinai peninsula would set us straight.

Upon setting foot in Dahab––which translates to ‘gold’ in Arabic––I was taken aback by its laissez-faire aura. This is not the conservative, rigid Egypt that comes to mind. (I had asked my Egyptian housemate, also a journalist, to describe her country in four words: chaotic, charming, rambunctious, and toxic, she shot back at me). Hordes of Caucasians in all degrees of beachwear dress and undress were abound; vegan options crowded the street food scene.

But dig just a bit beyond Dahab’s touristy surface, and you’ll find that the region’s Bedouin pulse remains strong. A culture strong enough to endure everything so far, from seemingly perpetual internecine conflict to frictions between modernity and the West and ancient traditions and beliefs.

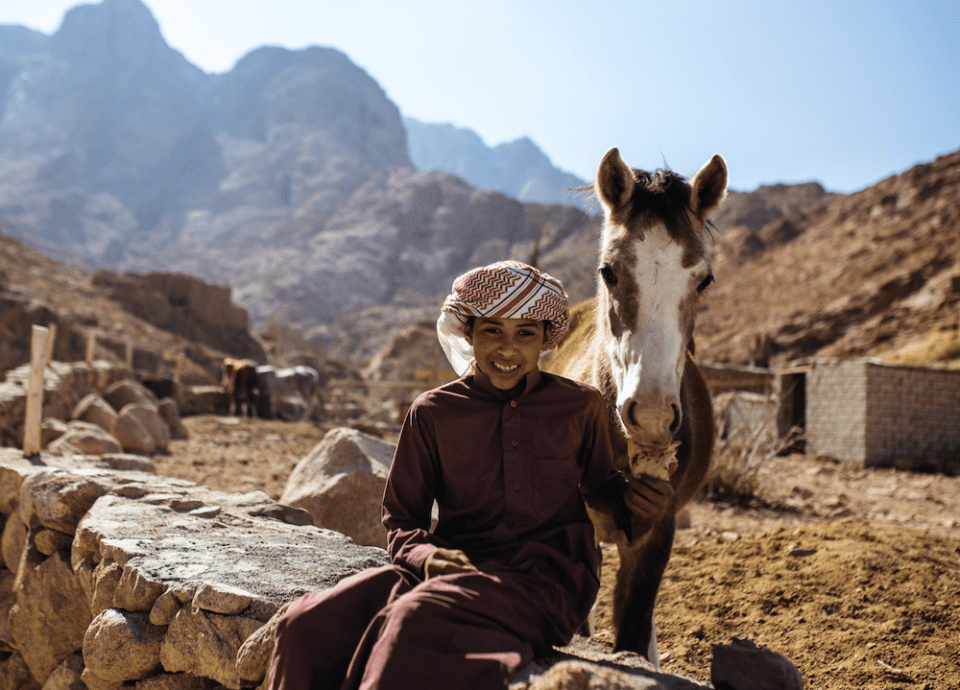

A bedouin boy and his horse at the base of Mt Sinai.

A bedouin boy and his horse at the base of Mt Sinai.

Regional history

The Sinai peninsula has always held strategic value and is one hyper-wracked with conflict. Tensions dating back millennia have permanently scarred ethnic relations between traditionally nomadic Bedouins and Egyptians. The country continues to process the identity conflict that is being both Egyptian and African. There’s also the risk of provoking its volatile neighbors, as the peninsula connects Israel and the Gaza strip to the Egyptian mainland.

Freedom of the press does not exist, my Egyptian housemate––also a journalist––will tell you, hence the lack of ground reporting. Just outside the euro-centric bubble of Dahab, police checkpoints are severe. On our way to Mt. Sinai in St. Catherine’s, the biblical site where Moses encountered the burning bush and received the Ten Commandments, we were nearly detained for packing whiskey in the trunk. The police stopping us seemed equally miffed and amused. Our hired driver made a call to let us off the hook and stayed on edge throughout the rest of the trip, happy to see us go. Honestly, we couldn’t blame him.

Dahab was traditionally a fishing village with a majority Bedouin population. The Bedouins are the original Arabs, nomadic peoples originating from Yemen who learned how to carve their homes out of the harsh desert climate.

Sinai’s Bedouins belong to the second exodus, where up to 17 distinct tribes emigrated to join extant communities nearly 600 years ago. Climate change and resource scarcity, in part due to the ballooning popularity of Dahab, means that today’s Bedouins frequently work with the tourism industry in some way. The town has since become one of the world’s top free-diving destinations.

But if there’s anything that we’ve learned about the fundamental sameness of the human experience, it is that people have largely the same dreams and desires. Particularly in a bubble such as Dahab, an oasis of respite from the intense authoritarianism dominating the rest of Egypt, a sport like climbing has the potential to gain momentum, weaving itself into the fabric of the outdoors scene.

Rock climbing Roots

Hailed for winter climbing in the sun on dry granite, Wadi Qnai boasts of sport routes and endless bouldering. Dahab climbing has even had the power to move people to change the course of their lives. This was the case for 30-year-old Menna Abdelrahman. She describes herself as someone who was never too sporty, yet started getting into long-distance hikes about 5 years ago. On an epic 17 night solo trip to trek Nepal’s Annapurna in 2018, it was the first time she experienced that high of an altitude, in that kind of biting weather. Although Abdelrahman was drawn to technical skills, given its scarcity in Egypt, she was hooked. She quit her corporate job in Cairo a few years later, wanting to do something different. She committed to moving to Dahab in 2019, which she said was “all about climbing.”

When asked about her personal relationship to the sport as a female in Egypt, Abdelrahman says that challenges she’s faced have less to do with climbing, and more of just being an Egyptian woman. “I grew up in a traditional, religious family household,” she says to me over Zoom. “It’s taken a lot of work to overcome certain perceptions over the years. Just being able to live in Dahab and travel has taken a lot of pushing to just do my own thing. But recognize how blessed I am with the privilege of having parents who budge.”

Max Weiner and Vassiliki Daskalakis preparing for a climb in Camel Canyon in Wadi Qnai.

Abdelrahman is drawn to the versatility of climbing: “It’s a sport that can be intense or mellow, depending on how you want to do it…There’s always something for me to improve on; I enjoy the flow the most.” Although she is working to build her technical sport skills, she has since fallen into bouldering and likes the experience of getting experience on the go. One of her favorites is Bedouin Cigarette, a crimpy 6a+.

Abdelrahman believes the grassroots climbing culture of Dahab sets it apart from the rest of MENA. “It’s a slow upward momentum,” she says. “We’re excited to see what direction the community takes in the future given the tangible progression we’ve seen over the past three or four years.” A member of the Women in the Wadi, founded by Egyptian American Amira Helmy, they work to cultivate the power of women coming together. “Without men, the otherwise inevitable gender dynamics are not even there to consider. It becomes more about our collective experience.”

Particularly in a bubble such as Dahab, an oasis of respite from the intense authoritarianism dominating the rest of Egypt, a sport like climbing has the potential to gain momentum.

As it is with most climbing communities in the world, Dahab climbers currently face access issues as they want to be left alone while enjoying the privilege of developing new crags. “Climbing is an incredible way to experience our environment,” Abdelrahman says. “A priority is to continue growing while caring for our environment.” She cites frustrations of dealing with the aftermath of negligent tourists, who enjoy catered Bedouin dinners in the wadis, yet will commit thoughtless acts of atrocities such as leaving candle wax in climbing holds. “I was so pissed,” she remembers.

As it is with many expatriate-heavy communities, it can be difficult to find consistency and dedication within Dahab’s budding climbing community. Its history only dates back to 1998, one initially catalyzed by expatriates. Around 2006, locals started getting into the sport, but the momentum was precarious. By the time Timo Elony moved to Dahab in 2017 with the express goal of developing the climbing there, the scene had more or less collapsed again. One of the founders of Red Sea Rock along with certified instructors Karim Sedky and Amira Helmy, Elony is committed to bringing Dahab onto the international tourism map through trips into both the known and unknown.

“There are always new wadis to explore and bolt. Just over the past few years, we’ve seen a tenfold increase in the climbing community here,” Elony says. “Corona helped, since some people had to stick around, but there’s also been more publicity through our Facebook groups––we try to regularly put out news––as well as the Ascent bouldering gym in Cairo.”

Hiking down Mt Sinai with a local companion––possibly the same location as the biblical Mt Sinai.

As the growing staple of climbers in Dahab continues nurturing their community, Elony says that it’s easier to find partners these days. It used to be mostly divers in the off-season who see climbing as an ancillary past-time, but there are increasingly more people with a streamlined appreciation for Dahab’s rocks.

The beauty of the region is that there is a myriad of styles. One can switch between sport, adventure trad climbing (beware of that sandstone choss!), and bouldering. “I find that people who stay longer tend to lean towards bouldering,” Elony explains. “It’s really good here, you can occupy yourself for months and months.”

The Red Sea Rock team has worked to establish a number of free guidebooks on routes in Wadi Qnai, Wadi Hamam, and Jebel Milehis, all less than an hour’s drive from Dahab, as a way to increase traffic while promoting best practices.

Wadi Qnai reminded me how we’re all very much in love with the mountains in our own ways. For climbers, it’s easy to convert the sport into an emotional crutch. You develop a special vibe with your most trusted belay partner, ideally someone who knows the right balance between pushing and comforting you. The blood pounding through your veins reminds you how alive you are; your brain ticks as you unlock sequences. Working my way up Burning Camel, a mega-classic crack (6a+) in Wadi Qnai’s Camel Canyon, it was a moment where everything felt right: the sunlight blazing down into the canyon, the novelty of cragging in North Africa, a pure joy of just enjoying the climb.

All photos by the author.