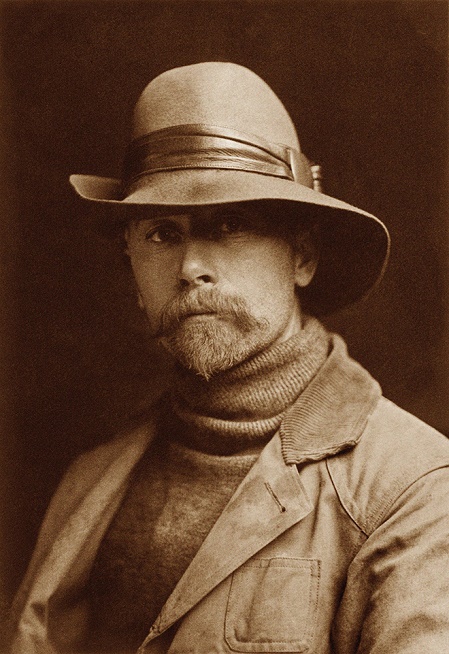

The man in the picture does not look like the bookish type. In a famous 1899 photo-a self-portrait in his trademark sepia-tone style-he sports a rakish felt slouch hat, turtleneck sweater, white canvas jacket, and Van Dyke beard, suggesting a better-groomed Buffalo Bill.

And yet, this former homesteader, this 6’2″, 30-year-old citizen of gold rush-era Seattle launched the most expensive and expansive book project by an individual, the largest ethnographic enterprise ever undertaken in this country: The North American Indian.

Between 1906 and 1930, he collected over 40,000 images from roughly 80 tribes. Of these, 1,500 silver-gelatin prints made the final cut for his magnum opus of oversize photogravure folios accompanied by twenty text volumes. The bound books alone take up five feet of shelf space.

Awed by the fledgling medium, photography, Edward Sheriff Curtis’ indigenous subjects nicknamed him Shadow Catcher-but the record he left is much more substantial. He augmented his pictorial hoard with Hopi vocabulary, with biographical sketches of Nez Perce chiefs, with information about all aspects of Lakota life. On more than 10,000 Edison wax cylinders, he preserved myths, stories, and music by peoples who, his fellow countrymen thought, would soon be extinct. But they survived Manifest Destiny, and some turned to Curtis’ collections to revive forgotten customs, to connect with a past that was quickly fading from view.

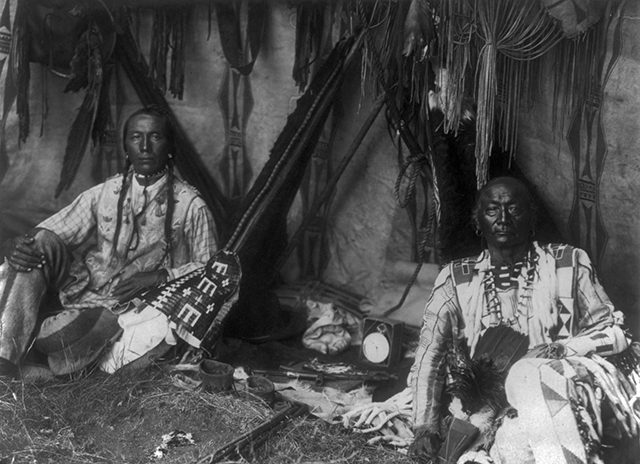

Little Plume and son Yellow Kidney seated on ground inside lodge, pipe between them. Curtis was criticized for removing traces of non-Native culture, like the clock, from his photos.

The man in the picture does also not look like a family man.

He was and he wasn’t. Footloose, a workaholic prone to depression, he sacrificed wedded bliss on ambition’s altar. In 1927, homebound from his last trip to Alaska, he was briefly arrested for failing to pay alimony to his ex-wife, Clara. At the time of his divorce seven years before, Curtis had been nearly broke; while he paid his assistants, he himself was unsalaried, investing any profits in his studio and equipment.

He’d long ago alienated his brother Asahel, who had preceded him to the Klondike, by not crediting him for his work there. Consequently, Asahel established his own studio in Seattle and became a known landscape photographer, booster for Mt. Rainier National Park, and founding member of The Mountaineers.

Still, throughout his life, Curtis remained close to his second child and oldest daughter, Beth, who funded his Alaska venture and became his studio manager after he moved to Los Angeles. His daughter Florence, who never really got to know her absentee father, urged him to write and record parts of his life story during his twilight years.

In 1898, as a budding photographer of Seattle’s elite, Curtis had joined the stampede to the Yukon goldfields. He’d returned with sets of glass-plate negatives that, he claimed, captured the mad rush “more clearly and truthfully than any mere pen picture.”

A chance meeting on Mt. Rainier’s slopes the same year had Curtis embark on his second trip to Alaska. When Curtis warned a party of climbers of dangers ahead, one of them struck up a friendship with the trim mountaineer. He was Clinton Hart Merriam, head of the US Biological Survey and co-founder of the National Geographic Society. After a tour of Curtis’ Seattle studio, impressed with his work, Merriam asked Curtis to be the official photographer for the 1899 Harriman Alaska Expedition. Steaming north through the Inside Passage on the luxuriously outfitted George W. Elder, Curtis met another fan of Alaska: fellow expedition member and Sierra Club founder John Muir. More important, however, was the mentorship he received from professional ethnographers onboard, which, three decades later, would culminate in some of his most celebrated work, gathered in volume XX of The North American Indian.

On the steamer Victoria, Curtis left for his second grand tour of Alaska in the summer of 1927, accompanied by daughter Beth and the young ethnologist Stewart Eastwood. He traveled less stately this time, on a tight budget. After arriving in Nome, the trio continued to Nunivak, King Island, Little Diomede, Kotzebue, Selawik, Noatak, and Cape Prince of Wales. Curtis had never been happier, as the Native culture there still appeared to be vibrant and Alaska reminded him of youthful adventures in the Pacific Northwest. For the first time in his career, he kept a day-by-day journal.

Nome, on the other hand, was but a husk of its gold rush self. Its population had shrunk from 20,000 to 750, most of them Eskimos. Stores, shops, hotels, and gambling dens housed only the wind. Sidewalk boards were broken or missing. Curtis bought a fishing boat, Jewel Guard, which came with its previous owner. According to Beth, the skipper-Harry the Fish, a Swede-hated liquor, tobacco, and women. The boat, about forty feet long, with a cabin, she deemed “not so bad.” Curtis, who had some experience with seagoing vessels, thought her “an ideal craft for muskrat hunting in the swamps but certainly never designed for storms in the Arctic Ocean.”

The locals had warned Curtis against pushing his luck by launching so late in the season. Foolhardy, perhaps, but with only the last volume left to be finished, Curtis insisted on one more adventure.

Less than a week out at sea, the travelers struck ice while a storm tossed them about. “The waves were ten times as great as our boat & we were shipping much water,” Beth wrote. When, after nearly capsizing, Jewel Guard stranded on a sandbar, Curtis waded away from the ship, set up his tripod, and snapped her portrait.

After visiting Nunivak and grim Hooper Bay-Curtis guessed that 75 percent of the residents suffered from tuberculosis-Beth had to return to Los Angeles. Curtis, Eastwood, and Harry the Fish labored on, to more remote communities. King Island, which Curtis described as a storm-beaten rock, in his opinion also was one of the most picturesque spots in the North. Like no other village on the continent, the settlement clung to precipitous cliffs, shored up by driftwood stilts. It lay ghostly abandoned, as its inhabitants now summered near Nome. Curtis hoped to interview King Islanders there upon his return, to fill in some cultural context. The photos he brought back from the island are haunting still lives, time capsules of a society whose gaze focused outward, onto the vast, immutable sea.

Anchored off Cape Prince of Wales, Curtis and his crew received visitors, “fully 50 of them”-walrus hunters in three large skin boats, who clambered on deck until Curtis feared that Jewel Guard would sink from the load. Curtis hired a local to act as interpreter at his next stop, Little Diomede Island. There, he got lucky with the weather, landed, and promptly went to work. The wife of a missionary told him it was the only perfect day that year, in fact, the finest she had seen in her four years on the island. Diomede’s population had been ravaged by a flu epidemic but the honeyed, late-summer evening light must have thrilled Curtis-he worked sixty hours for each four he slept.

Storms caught up again with Curtis at Kotzebue, where a pilot he’d hired got them mired and lost in the mudflats. The pilot later admitted that he knew everything there was to know about driving dog teams but not much about guiding big boats. A canoe excursion took Curtis and Eastwood to Noatak Village, where both worked hard for several days; Curtis still found time to praise “the fine flavor of Noatak salmon trout” [steelhead or anadromous rainbow trout].

Curtis and his company only left Kotzebue in September. The days were getting short, the barometric pressure was falling, and the locals were putting up boats for the winter. Harry the Fish frothed at the gills, because they had not sailed sooner. On their return trip, a blizzard promptly assailed Jewel Guard. Encased by an ice membrane, she was at risk of freezing in place until spring. Then her hull sprang a leak, and the sea started pressing in. All hands shoveled snow off the wallowing bow and bailed a foot of water from the galley. Like a crippled seabird, Jewel Guard limped back to Nome, where her crew had been given up for dead. Curtis, however, was stoic. “You either make it or you don’t,” he wrote in his journal. The main thing, he felt, were the images he had secured, the capstone of his career and some of his best work.

Seen from a strictly commercial perspective, Curtis did not make it. After Alaska, he surrendered the rights to his work to industrialist J. P. Morgan’s son, who kept funding the costly printings. The man Theodore Roosevelt once endorsed would die penniless, friendless, at age eighty-four, forgotten by almost everyone.

Though belated, the ultimate praise for his life’s work came from those whom Edward S. Curtis sought to honor. “Never before,” writes Kiowa author N. Scott Momaday, “have we seen the Indians of North America so close to the origins of their humanity.” Despite its romanticized angle, Curtis’s obsession has given us “indispensable images of every human being at every time in every place.”