Did ya know — AJ has nearly 5,000 stories in our archive? We’re busily working on a redesign of our website to better feature stories from the past so that new readers — or veteran AJ lovers who missed ’em the first time around — can enjoy. Like this story from 2018 that stoked debate about climbing etiquette. -Ed.

All climbers have their list of personal pet peeves—for many of my generation it starts with groups of ten or more, never having done a multi-pitch climb, lining up for the North Chimney of Castleton Tower. (“Hey, it’s only 5.9 right?”) For younger climbers, it’s close-minded curmudgeons such as myself who prattle on endlessly about the good old days.

One thing everyone can agree on is that things have changed. In the early 1970s, Yvon Chouinard observed that climbers were primarily a bunch of guys who couldn’t get a date. We were struck dumb if a woman ever showed up carrying rock shoes. We still believed that the leader must not fall, while today the rule is if you’re not flyin’ you’re not tryin’.

Looking back, I believe my partners and I were probably too scared of climbing’s risks, but watching climbers today I sometimes feel they don’t take the risks seriously enough. Inattentive belaying, uneven ropes on rappel, poor communication, unfinished knots, and the improper use of gear can get people killed.

But when talking about what’s annoying, it’s worth considering that pretty much any habit becomes a bad habit when multiplied by 10, 15, 20 or more individuals. There is an adage in land management that if users can’t manage themselves, they need to be managed. This means that if climbers want to avoid ever more regulations, it’s imperative that we recognize the impact our growing numbers have on each other and the places we climb.

In that spirit, here’s a list of bad habits we should recognize and try to break.

1. Monopolizing the Route

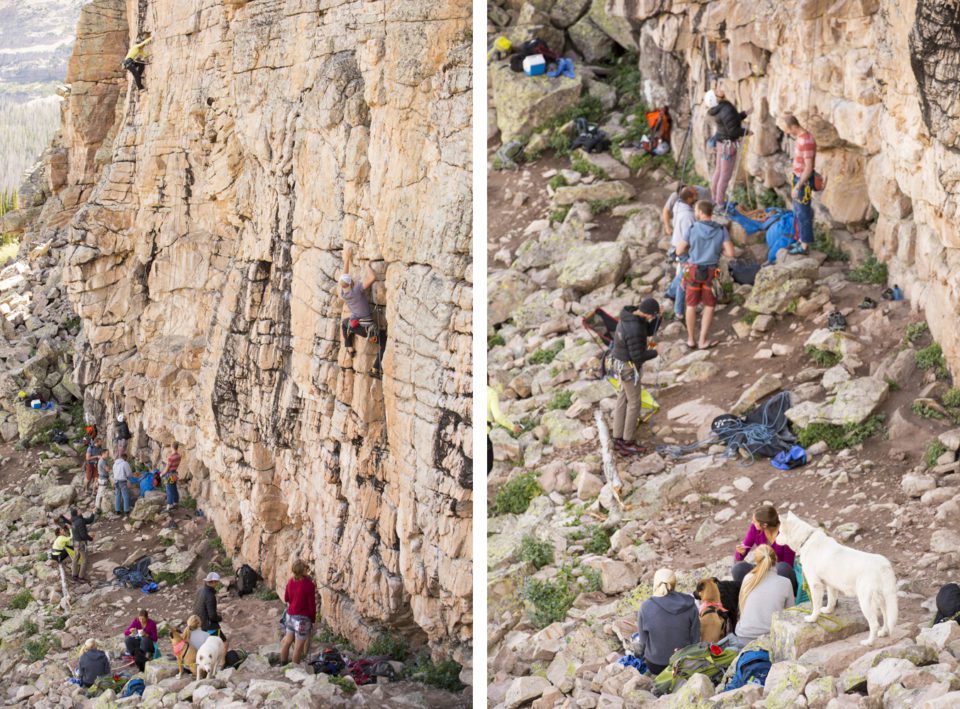

Anyone who has visited a popular climbing area in the past few years has witnessed one or more parties siege top-roping a route or an entire section of cliff for hours on end.

This particularly irritating habit has reached its zenith in Utah’s Indian Creek where large groups not only bogart a route, they often save it for friends who haven’t even arrived.

Solution: Remember the public in public lands. Climbing crags are a shared resource so come ready to share. If you’d like to keep working a route, allow waiting parties to take their turn, then if no one else is waiting, politely ask them to re-hang your rope and draws. And keep in mind, people who are not physically present never have precedence over those who are.

2. Top Roping Through Fixed Anchors

When the Access Fund polled local climbers’ organizations about the habits that drove them nuts, bogarting and toproping through fixed gear topped everyone’s list. If you’ve never put up a sport route, you don’t know how expensive it is. A friend of mine who has put up hundreds of new routes estimates that he has invested more than $40,000 in bolts, hangers, chains, and drill bits. Outdoor crags are not like gyms, where everyone pays to climb and therefore shares in the cost of replacing worn gear.

Solution: When top roping, always run the rope through your own personal carabiners at the top of the route.

3. Being Loud

I asked my climber friends what pissed them off the most and guide Lindsay Fixmer didn’t hesitate before denouncing loud music at the crag, stating vehemently that “under no circumstances should reggae ever be allowed and definitely no Grateful Dead either.” However, N.W.A. is fine. Lindsay was kidding (sort of) but her response illustrates the dangers of relying on personal taste when defining bad behavior. Don’t assume that others share your highly refined taste in music, wine, or anything else.

Solution: If you must have music when you climb (and ear buds just aren’t good enough) ask everyone within earshot if music bothers them. And if they say yes, be willing to turn it off or move on. Even better, open yourself to the radically healing and transformative experience of the stillness of nature and save Rihanna for the drive home.

4. Flying Drones

The bad habit of using drones to shoot climbing video is a sub-category of noise but with the added irritation that it’s also an invasion of privacy. No one enjoys having a giant mechanical insect buzzing near their shoulder as they search frantically for the next mono.

Solution: If you must fly a drone, talk to everyone. Explain what you’re up to and how long you’ll be filming. Do your business quickly, then pack it up. Never film anyone without permission.

5. Bringing Dogs

Just because you like dogs, doesn’t mean it’s a good idea to bring one to the crag. This topic is as polarizing as guns in America, I know, but limiting dogs at the crag can be for their own good. Zoaster Toaster, one of the most popular routes in Utah’s Maple Canyon, got its name when a dog named Zoaster was frolicking below as the route was cleaned and bolted. A cobble the size of a grapefruit fell from the wildly overhanging wall and clocked Zoaster directly on the noggin.

Zoaster went down and everyone thought it was for good. However, after about 10 minutes the mighty pooch rose from the dead and resumed his romping as though nothing had happened. But still.

Solution: In your heart of hearts you already know whether your dog is “crag worthy,” but just to make sure check out this excellent blog post from the Access Fund on how to responsibly bring dogs climbing.

6. Faulty Parenting

Combining kids with climbing is another emotionally charged minefield. On one hand, we want our kids to experience and fall in love with the activities and places we love and that enrich our lives. On the other, no one ever wants to see kids having a lousy time, or worse yet get hurt.

A few years ago I was trad climbing in Utah’s Little Cottonwood Canyon. As I started the second pitch I heard a commotion. Looking over to the next route, I discovered a young couple a rope length above the ground frantically shouting down to their two small children who were playing unattended at the base of the cliff. It turned out that the kids were playing with a good-sized rattlesnake.

If one learns to climb in a gym it’s conceivable that you might make the mistake of assuming that because climbing gyms are relatively safe, controlled, and kid friendly, then climbing outside must be as well.

The main issue is safety. Sure, badly behaved kids can be annoying, but that’s nothing compared to the acute discomfort of watching children placed in harm’s way. And please don’t think that putting a helmet on a child protects them from rock fall. Helmets can protect against small stones, but a direct hit from a rock of more than a few ounces can be fatal for children and adults.

Solution: When you take the kids out, your mission is one hundred percent ensuring their safety and providing them with a good experience. This means choosing crags wisely, keeping children and their toys well back from danger zones, and teaming up with other parents or others who are willing to watch the kids while you pull down. Oh, and did I mention to bring plenty of snacks? The dogs at the crag will love them.

7. Inappropriate Poop Management

Jeff Pedersen, founder and CEO of Momentum Climbing Gyms, told me a story that illustrates the potential risks of outdoor sanitation. Back when he was a full-time climber, Pedersen had an ongoing argument with a friend about the proper way to dispose of used toilet paper at the crag. He said the best method was to bury it, while his friend said burn it.

One summer the two were working a route near St. George, Utah, but first Pedersen’s partner had to answer the call of nature. A few minutes went by and Pedersen turned to discover the entire hillside below engulfed in flames. His buddy had set a match to his toilet paper and a gust of wind had carried the flaming wad into tinder-dry grass.

Years later, Pedersen remembers, “Forget the send. We spent that entire day chasing burning embers. We had to take the floor mats out of my truck and use them to beat out the flames. By the time we got the fire out we were so torched ourselves we didn’t have enough strength to climb 5.7.”

Solution: Lacking an outhouse, the best method is to use a disposable wag bag and carry your waste out. For more on this and other ways to lessen your impact, refresh your knowledge of the Leave No Trace principles here.

8. Mansplaining

I include this as a public service to male climbers of a certain age, dudes who’ve been climbing most of their lives but think nothing notable has happened since Warren Harding climbed the Dawn Wall. If women want pointers about where the nearest 5.8 classics are located and how to properly climb them—and they probably don’t—they’ll ask.

Solution: Stop. Just stop.

Being a good climbing citizen distills to living by the golden rule. Be considerate of others. Cultivate self-awareness. Ask yourself if your behavior could annoy those around you, and if so whether there’s an alternative? Be outgoing and friendly. And remember that one of the best things about climbing is climbers. Life-long climber Jim Donini, 73 this year, never complains about the increased numbers in his beloved Indian Creek. He’s too busy making new friends.

For more on how to improve everyone’s climbing experience, I urge you to read and sign the Climber’s Pact, found right here at the Access Fund. And please support the Access Fund and your local climbers’ organization.

Chris Noble is the author of two books on climbers and the climbing lifestyle, Women Who Dare and Why We Climb. Photos by the author.