As a financial strategy, there’s a certain logic to taking bets that you are about to die. If you survive, you’ve just made a bundle of money. And if you die, losing the bet is the least of your worries.

Welcome inside the enterprising mind of Al Faussett, the lumberjack-turned-daredevil who was first to run 104-foot Sunset Falls back in 1926.

“There is nothing to be afraid of, for I have studied the dangers carefully, and I believe I can negotiate these falls where 20 men have lost their lives”

Faussett survived the plunge in a 32-foot spruce log he’d hollowed out and reinforced with steel cladding. The finishing touch was an array of stout vine maple branches protruding at angles from the canoe so that it would glance off of rocks. A good plan, given that most of the Skykomish River pummels straight into a massive boulder about two-thirds of the way down Sunset Falls, which is not a proper waterfall at all, but what whitewater boaters call a slide. It drops 104 feet over the course of 275 feet and is mined with all manner of deadly hazards. The entire right side is a hungry sieve. On the left is that boulder, spouting a huge rooster tail as the river plows into it at about 60 miles per hour. Below that it’s hard to say what lies under the frothing mass of white foam. It’s not good.

Faussett’s blithe assessment of the gauntlet only proves how little he knew about what he was getting into. “There is nothing to be afraid of, for I have studied the dangers carefully, and I believe I can negotiate these falls where 20 men have lost their lives,” Faussett told Everett News sports reporter Herbert “Scoop” Toole, who doubled as his publicist.

That Sunday, May 30, 1926, he was more concerned with freeloaders in the crowd than the details of his craft or the whitewater gauntlet he was preparing to run. Newspapers estimated 3,500 to 5,000 people had come to watch him “cheat death,” but it was Daredevil Al who got cheated. He’d planned to charge spectators a dollar per head but had failed to cordon off the riverbank. Thousands of onlookers slipped through the woods, avoiding his ticket booth.

Faussett delayed the attempt three hours as he tried to scheme a way to make them pay up. Finally, out of ideas, he shoved off. The Skykomish Queen lumbered into the current, gathered speed and shot down the slide. The vessel slipped by the roostertail, disappeared for a long count and finally emerged, unscathed, in the pool below. Faussett popped his head out and waved triumphantly.

(Sunset wasn’t attempted again until 2008, when local kayaking legend Rob McKibbin ran it on his lunch break, blowing his spray skirt and swimming at the bottom. Tyler Bradt claimed the first clean kayak descent the following year.)

When Toole caught up with him Faussett told the newspaperman that the line to his homemade air tank separated and he was forced to hold his breath as best he could against the crushing water. The water came so fast it crammed down his nostrils and throat and yet, he assured the scribe, “At no time was I afraid of those treacherous falls, not even when the water seemed to be crushing the very life out of me.

“It was all over in a few seconds, and when I saw the light of day as I rode out of the turbulent waters, I thanked God that I had ridden safely through. Would I ride it again? Yes, I would, but never will I ride Sunset Falls or any other falls unless I see the color of the money first.”

The career of the world’s most prolific whitewater daredevil was underway.

Faussett was the eighth of ten children, born to Irish immigrants in 1879. The family was poor but ambitious, and some of Faussett’s brothers found success in real estate and the law. As a young man, Faussett worked as a tree feller and kept a steady sideline of stunts and wagers. By the turn of the century, “bettors came from all around to compete with Al’s horses, or to wrestle, box, and participate in footraces with this cocky young man,” according to his History Link biography. Newspapers often reported that he was afraid of the water, but that was pure hyperbole. He was a fine swimmer who once saved his sister and her baby from drowning.

Years later he wrecked the family car on when, on a bet, he built a ramp and tried to jump it. Such antics were tough on relationships, and Faussett was twice married and twice divorced. His second marriage ended in 1925, the year before he shot Sunset at the relatively advanced age of 47. According to some accounts, Hollywood producers had offered $5,000 to run the falls in a canoe. The legend persists, even though Toole took pains to debunk it the morning after the stunt, noting in the Everett News that “no deal had been closed with any movie concern and Faussett will derive no funds from that source.”

Faussett wasn’t completely skunked though. According to his great-grandson Guy Faussett, those bets on whether he would survive paid off to the tune of about $1,500. He immediately set his sights on bigger prizes, announcing plans to run 268-foot Snoqualmie Falls near Seattle, followed by Niagara itself.

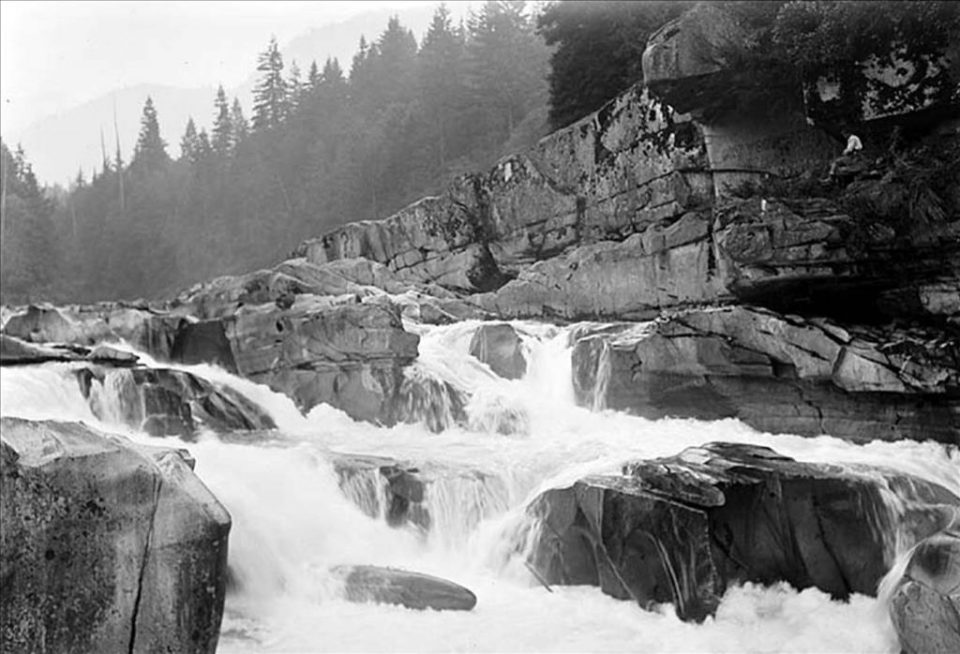

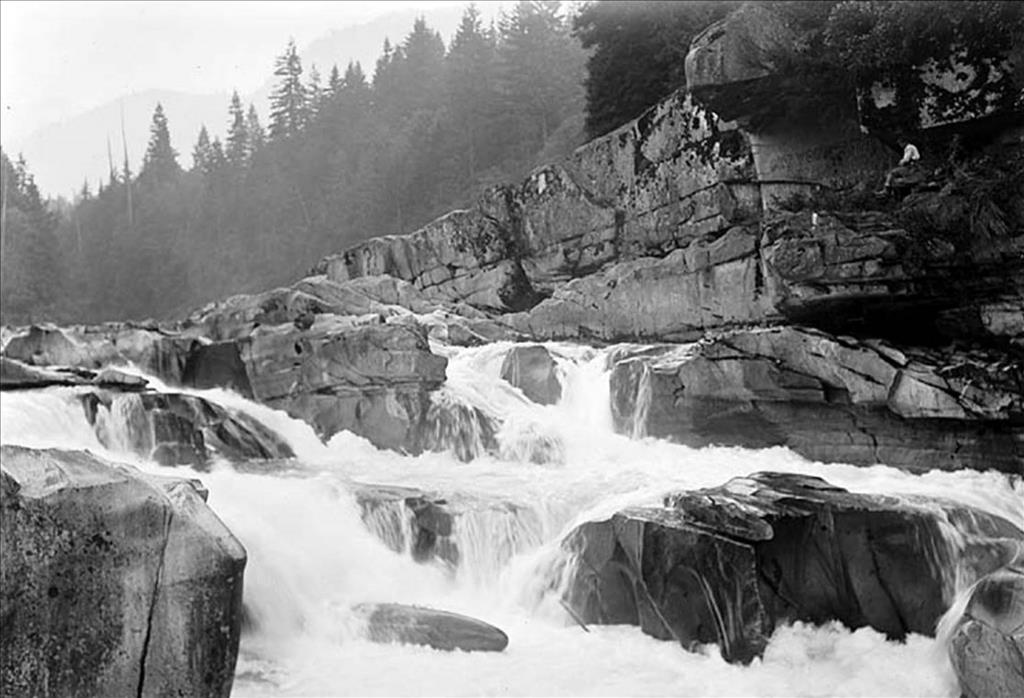

In modern parlance, Eagle Falls is a mankfest. Faussett pinned midway down. Photo by Lee Pickett, Courtesy UW Special Collections

In modern parlance, Eagle Falls is a mankfest. Faussett pinned midway down. Photo by Lee Pickett, Courtesy UW Special Collections

County commissioners denied him permission to run Snoqualmie on the grounds that there was no fence to prevent spectators from falling over the edge, so Faussett settled for 28-foot Eagle Falls instead. The drop is on the South Fork Skykomish a few miles upstream of Sunset, and despite its relatively modest height its array of midstream rocks presented some challenges to the daredevil. Faussett dropped it in another homemade craft, this one a 16-foot cigar-shaped affair reinforced with steel hoops, like a barrel. He ran the falls on Labor Day, 1926.

His strategy: close the hatch and let her rip.

Midway down, the contraption pinned on a rock. After some time, Faussett opened the hatch and hollered to friends on shore, who eventually dislodged the craft with pike poles. About 400 people witnessed the event, according to Toole’s charitable account in the Everett News. “The water was low and showed many jagged rocks on the perilous descent but Faussett’s specially constructed canoe made the hazardous trip over the angry looking ‘white water’ without mishap,” he wrote.

Next up was Spokane Falls, a pair of diversion dams in the city’s downtown with a combined drop of 146 feet. Faussett built a 15-foot spruce dugout for the June 1, 1927 stunt, reinforced it with iron bands and fixed oak roots to the bow to deflect impacts. He christened it the “777 of Seattle.” The auspicious craft was fully enclosed and fitted with a trapdoor, but on the day of the stunt Faussett and his helpers couldn’t get it across the powerful eddy line and into the river’s main flow. It spun four times and drifted to a halt as an estimated 20,000 to 40,000 people watched. Faussett then opened the hatch and asked for a rope, pulling himself hand-over-hand into the current, which seized the boat and spun it wildly. Water gushed in, filling the boat perhaps half full. Faussett called for another rope, but it was too late. “The current snatched his vessel and propelled it into the Upper Falls,” according to Phil Dougherty’s account on History Link.

“The boat shot nearly 20 feet into the air and then flipped end over end before landing at the bottom of the falls and disappearing for nearly a minute. The crowd shouted less than reassuring comments back and forth: ‘He’s a goner,’ ‘He won’t make it,’ and ‘You’ll never see him again.’ Yet the boat did reappear, ‘for all the world like a breaching whale,’ described the Spokesman-Review, only to get sucked into another whirlpool and spun from the south to the north end of the river, whirling like a spinning top for a good 10 minutes,” Dougherty writes.

Faussett finally escaped the craft and rescuers fished him out of the pool between the two falls. His boat, the lucky 777, spun there for hours before finally sliding over the lower falls and smashing into pieces, the largest of which the Spokesman-Review reported was five feet long and four inches wide. Faussett himself suffered lacerations and a concussion. On the way to the hospital he told the ambulance driver to take it slow, according to the newspaper’s fanciful account. “Slow’er up a little, buddy, take it easy an’ be careful,” he reportedly said. “It pays to be careful—you can’t be too careful, no-sir-ee, yuh sure can’t.”

Faussett ran 177-foot South Falls in a canvas shell stuffed full of inner tubes. Courtesy Travel Oregon.

Faussett vowed to return to Spokane Falls but never did. Even he wasn’t that crazy, but he wasn’t finished either. The following March, he rode another spruce dugout over a rain-swollen Willamette Falls south of Portland, Oregon. The awkward craft slipped sideways over the first 20-foot ledge and was held under for about three minutes, according to the Associated Press. “One hundred and fifty feet beyond the falls, the white boat shot out of the foam and spray for a moment—then crashed into another curtain of foam and was lost again. At the foot of the rapids the canoe appeared again, turning over and over.” Faussett soon emerged, battered, triumphant and talking about his next big stunt.

He’d found the perfect venue in 177-foot South Falls in Oregon. It offered a clean drop of headline-grabbing height. Best of all it was on private property, meaning he could make sure everyone who watched the stunt paid for the privilege.

He struck up a partnership with landowner Daniel Geisler, who already had some experience in the promotion game, charging people 50 cents a head to watch him push junk cars over the edge of the falls. Geisler liked Faussett’s plan but was worried about liability, so the two men made a deal. “Al would ‘buy’ the falls and surrounding land, own it for one day, and Geisler would ‘buy’ it back after the stunt (or inherit it in Al’s will, if things went really badly),” according to writer Finn John’s account.

Faussett took a completely new approach to the July 1, 1928 stunt, using a small canvas boat stuffed full of inner tubes. To make sure it would clear the rocks and enter the water nose-first, Faussett had run a guide cable from top to bottom, but on the way down the craft snagged on a splice in the cable. The line snapped and the craft landed flat, like a bellyflop. Faussett suffered two sprained ankles, a broken wrist, two fractured ribs, and internal injuries. Worse, his manager skipped town with the gate, an estimated $5,000. Faussett didn’t see a penny.

Faussett ended his waterfall career in 1929 with uncharacteristically smooth descents of 212-foot Shoshone Falls in Idaho and Celilo Falls on the Columbia River. His waterfall-jumping system was finally dialed, but the daredevil game just wasn’t penciling out. “Gate receipts just wouldn’t cover his construction expenses and hospital bills,” Johns writes. Faussett continued to tinker with plans and talk about the big one, Niagara, but he never ran another waterfall. He died in bed in 1948, aged 68 years.