It’s the sort of caper any kid could dream, but only a billionaire could pay for: Circling the globe in life-sized Tonka trucks and touching both the north and south poles in the process. The dreamer is one Vasily Shakhnovsky, described on the expedition website simply as “Retiree. Traveler. Initiator of the expedition.” There’s a bit more to him than that.

Back in 2003, when Forbes tallied the Russian oil baron’s fortune at $1.8 billion and his business partners landed in jail for extortion, murder and, most egregiously, crossing Vladimir Putin, Shakhnovsky paid a modest fine for tax evasion and retired to Switzerland.

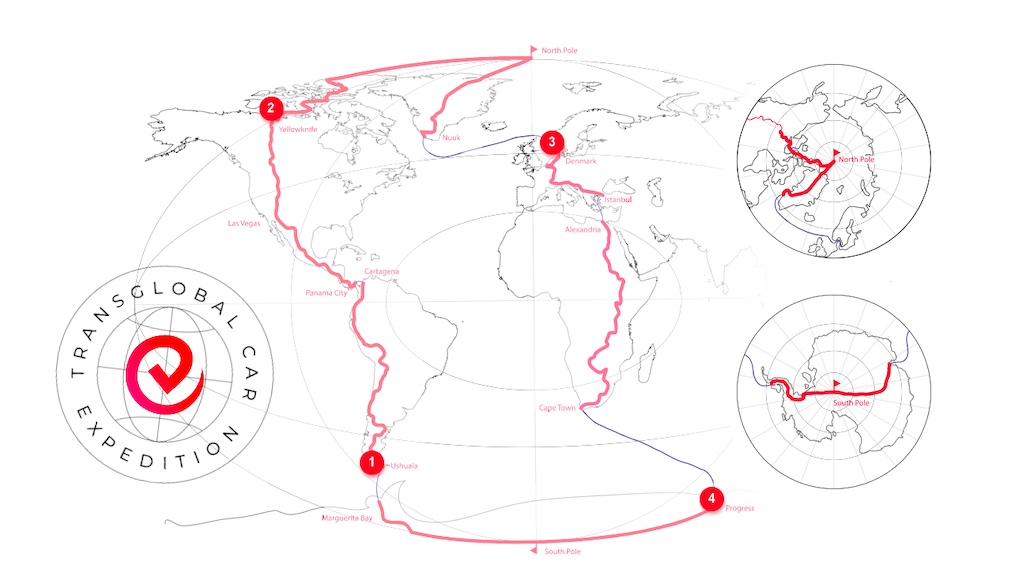

In his new career as a traveler, his ambitions have focused on the 25,000-mile Transglobal Car Expedition across five continents and both poles. The trip is supposed to kick off in September 2022 and finish 16 months later. In the meantime, Shakhnovsky and his team traveled to the Canadian Arctic to work out how to drive across a few hundred miles of frozen ocean.

This sanctions-busting selfie was a poor start, but sinking a pickup in pristine Arctic waters really wore out the team’s welcome.

This sanctions-busting selfie was a poor start, but sinking a pickup in pristine Arctic waters really wore out the team’s welcome.

The expedition’s supporting cast includes a Canadian rally-car driver turned stuntman, a handful of accomplished alpinists, and a mad-scientist adventurer who builds six-wheeled amphibious super-trucks. Also on the team is Emil Grimsson, the mastermind behind those jacked-up Icelandic overlanders you see on Instagram. A Toyota man all his life, lately he’s been working on a Ford F-150 version with 44-inch tires and, presumably, a seriously upgraded heater.

It was Grimsson who got stuck talking to the press after one of the rigs dropped through the sea ice, leaving nothing but a truck-sized hole and one lonely tire to mark its passing. But we’re getting ahead of the story.

Let’s back up to the first of March, when Shakhnovsky and pair of sidekicks jetted from Switzerland to Yellowknife for the start of the 1,500-mile “Canadian Test Drive” from there to Resolute, Nunavut.

Vladimir Putin had sent his army into Ukraine just days earlier, prompting Canada, the United States and other governments to close their airspace to Russian aircraft. Shakhnovsky and his henchmen disregarded that inconvenience, jetting from Geneva to Yellowknife in a chartered Falcon 900, for which Canadian authorities issued a polite tongue-lashing and an $18,000 fine. This is a laughable amount if you’re a billionaire, or even a billionaire’s crony, as evidenced by their lol-ing on social media.

The main event is a 16-month, 25,000-mile circumnavigation touching both poles.

Still, the situation was tense enough that Shakhnovsky decided to quietly exit the country, and leave the Canadian trailblazing to his henchmen. “Ironically, had he flown commercial, he would have been fine,” said the stuntman, Andrew Comrie-Picard.

Within a week, a team of 16 began the long drive from Yellowknife to Resolute in four Yemelya overlanders and three highly modified F-150s. One of the Russian mega-rigs towed an elaborate radar array to measure the thickness of the sea ice, which the expedition graciously planned to pass along to the Native people across whose territory they were cannonballing.

“We are hoping that on this trip, the ice data we are collecting will be helpful to communities,” Comrie-Picard told the Nunatsiaq News.

In retrospect, the adventurers should probably have asked the local people what they knew about ice conditions. No one did, and now a very expensive hunk of metal is leeching fuel and other toxic chemicals into the waters Native people rely on for their livelihoods.

“We live off the land. We’re not farmers. We’re hunters and gatherers, and we need our game to be clean,” Jimmy Oleekatalik, manager of the hunters and trappers group in Taloyoak, Nunavut, told the CBC.

Expedition members said the ice was half a meter thick when the team passed between the Tasmania Islands on the way north. After reaching Resolute the team split up, with some staying in the northern outpost with the Yemelyas, and others doubling back to Yellowknife in the two remaining Fords (the third F-150 had dropped out earlier due to mechanical issues). When the F-150s backtracked to the same area five days later, they said they were “shocked” to discover the sea ice was a mere 15 centimeters thick.

Shocked, I tell you.

Not Oleekatalik. “They should have consulted with us,” the hunter said, adding that the community would have happily provided a guide. “This is our hunting ground. This is our livelihood. This is what we know.”

The three Arctic Trucks modified F-150s in happier times.

In fairness, the team did have a Nunavut member. A hunter hired to fend off polar bears and other curious wildlife was in the blue Ford when it crashed through the ice half an hour before midnight on March 23, along with driver Torfi Johansson of Iceland. Both scrambled out the passenger side door as the truck listed hard, then plunged through the ice. It’s still on the bottom of the Arctic Ocean with about 40 liters (10.6 gallons) of fuel aboard, according to a report the team called in to a spill hotline. The other F-150 was breaking trail and hauling most of the expedition’s fuel. Fortunately it did not fall through, but the team spent a nervous few hours on thin sea ice, huddled in the one remaining rig. A helicopter flew them out the next day.

The expedition members have since scattered home to Russia, Iceland and other parts of the world, making no concrete plans to repair the damage. Grimmson said the team was “very likely” to recover the truck, but was careful to make no promises. The rig is lying about 35 feet under the surface, so recovering it should not be a tall order for someone with a wallet as fat as Shakhnovsky’s.

Regaining the trust of local people won’t be so easy. Hubris doesn’t play well in northern communities, and it’s a liability for explorers as well. That lesson is at least as old as Amundsen and Scott’s 1911 race to the South Pole, said West Hansen, whose mission to kayak the entire Northwest Passage will take him through the Tasmania Islands late this summer.

“The most successful explorers learn from those who have come before them,” he said. “Amundsen spent three years in the Northwest Passage, coincidentally just a few miles south of where that F-150 sank through the ice, learning from the Inuit how to survive and thrive in sub-freezing temperatures. Scott, on the other hand, relied on untested scientific theories and a sense of technological superiority.” While Amundsen’s open-minded approach brought him to the pole and safely home, Scott’s failure the same season owes much to his hubris.

The team’s Yemelya ATVs don’t have heated seats, but they float.

“At its core, that’s what figuratively and literally sank the global pick-up truck drivers,” Hansen said. “They didn’t consult the locals, nor did they do enough research to figure out that driving a two-ton vehicle over ever-thinning sea ice is a really bad idea.”

Whether that lesson has penetrated the expedition’s inner circle remains to be seen, but the Canadian Test Drive produced one irrefutable takeaway. “It is difficult to guarantee the safe passage of the Cambridge Bay-Resolute section by vehicles that do not have positive buoyancy,” blogged expedition member Vasily Elagin. He’s driven to the North Pole twice in his plodding Yemelya vehicles, which have just one feature the optioned-out Fords lack: They float.

The Transglobal Car expedition is scheduled to start its pole-to-pole circumnavigation from Ushuaia, Argentina, in September.

Photos via Instagram and transglobalcar.com. Top photo: A Viking funeral for the Blue Ford.

Read more :

- A Historic Chance to Protect America’s Free-Flowing Rivers

- A Hypocritical Oath: When Environmentalism Doesn’t Extend to Favored Toys

- Wilderness Guides Lead Winter-Long Snowshoe Epic Across Ontario

- Over Half of U.S. Waters Are Too Polluted to Swim or Fish

- It’s Not a Real Baja Trip Until You Mess Something Up

1 comment

I believe this website has some really excellent information for everyone. “The penalty of success is to be bored by the attentions of people who formerly snubbed you.” by Mary Wilson Little.