Every so often you come across a true story so wild you couldn’t make it up.

Aaron Carotta’s story was one of those. In 2016 he started down the Missouri River with $37 and a borrowed canoe. He made it to Florida 233 days later, which is not nearly so remarkable as the way that he did it. Starting with no experience and not much of a plan, he learned to survive by putting his trust in others, passing from one river angel to the next along America’s longest river system and the Gulf of Mexico.

I got the sense then that Aaron had no choice. He had just beaten cancer and was fresh out of a marriage that had lasted just 14 days. He needed the river to regain his equilibrium.

Fast-forward six years. Aaron got his mojo back, but lost the thread when he left the river. There was a job as a local newscaster, a year-long pursuit covering 120,000 miles and ending in a Florida hospital, and time at his family home, where he’s no longer welcome. Never mind the details. Let’s just say you couldn’t make those up either.

Then, one night in Southern California, he heard the ocean calling. “I had a moment where the seas parted and I was standing on the beach at 8 or 9 p.m., gravitating towards the water and hearing ‘Come. It’s safe. I want to help you. You need to do this.’”

Aaron acquired a secondhand ocean-rowing boat for pennies on the dollar and spent the next year preparing it to carry him around the belly of the world. He started from San Diego in October 2021, before all the needed work was done, with $5 in his pocket, a rudder patched with duct tape, and a passenger he’d met in a barbershop. She lasted 36 hours. Aaron Carotta is still at it, despite an apparent heart attack, near starvation and a rescue he had to be talked into. Adventure Journal caught up with him in Zihuatanejo, Mexico, where despite everything he’s preparing to press on, first to Panama and then across the Pacific.

Carotta’s ocean-going rowboat Smiles on the beach in Bahía Asunción, Baja California Sur, approximately 500 sea miles south of San Diego.

Adventure Journal: You began your 5,000-mile canoe trip with $37 to your name, which seemed pretty remarkable until you started rowing around the world with $5 in your pocket.

Aaron Carotta: After having cancer in 2008 I traveled to 80 countries around the world. In my first country, Costa Rica, I jumped off some waterfall that people didn’t think you could jump off, and somebody said, ‘Hey it’s Mr. Adventure!’ I thought there’s no way I would ever be able to live up to that—my name’s Aaron. And from that point on Adventure Aaron became me.

It keeps me just in such a pure place when I’m in that adventure life mode, and it’s been trial and error when I’m in postpartum adventure. It comes full circle because it’s my way of life. And that’s kind of how it’s been funded and allowed me to keep going all-in—because it’s my life.

When I got the boat it had a hole in it and a broken rudder. So I took it to the bayou. I learned how to fiberglass. All the electronics needed to be fixed, so I learned electricity. Then when I got it to San Diego, I duct-taped the rudder and got it to Bahía Asunción.

I didn’t tell anyone that because I know there are people who are going to shun me for even getting on the water. But that was the only means I had, and I knew that if I got it out of the States I can cost-effectively fix things, take my time and also interact with the locals and give them the donor connection from my cause. That’s the beauty of it, connecting the first world with the Third World, where $150 in repairs eliminated the $3,000 or $5,000 that it would have cost in San Diego, and prevents most people from doing these things.

I used to wonder why I’m not sponsored, when other people are on social media these days raising thousands, hundreds of thousand dollars? Now it’s just me personally trying to figure out the tug and pull, if you will, with myself and how that spirituality quest coincides with people in the world who operate on a business mode. So staying lawful and staying spiritual are two rules that I have moving forward because in the past, if any of that is jeopardized, then all the good I’m trying to find and seek and share gets tampered with.

So it’s a spiritual quest?

Absolutely. It’s first and foremost. And what happened out there at sea for 36 days trying to cross the Sea of Cortez, I had those moments that you hear about from other people who are lost at sea or that almost died. That brought that purity back to my life.

I was raised Catholic, so it’s under the Christianity umbrella in general, but I don’t really subscribe to all the details that come with each different religion. Traveling through so many countries, I have one-loved and adapted to everyone’s beliefs and try to understand them. I just really believe in a higher being.

I spent time trying to understand why, after my canoe journey, I was prescribed meds that were more actual drugs than the route that would heal me. I started digging and what I uncovered was a level of consciousness that healed me to get to this journey. I literally went to the ocean, Balboa Island, after the locals thought I was crazy, probably called a wellness check up on me. And I had a moment where the seas parted and I was standing on the beach at 8 or 9 p.m., gravitating towards the water and hearing ‘Come. It’s safe. I want to help you. You need to do this.’

At that point, I called my guru Hare Krisna friend in New Zealand, and she was the number-one person that said, ‘Go, this is 100 percent right. Do it.’ And for the next year, I spent planning it with Chris Martin, of the Ocean Rowing Society.

You mentioned something a moment ago that caught my attention: postpartum adventure. I think most of us can relate to the letdown after the magic of a trip like your canoe expedition from Montana to Florida.

I remember talking to Big Muddy Mike Clark, who I still love dearly, and another friend named Rich Brand who circumnavigated the U.S. on the Great Loop.

Rich called me and said, ‘Aaron, when you finish your trip in the next week or two and you have that moment, call me.’ And then Mike told me, ‘Make a to-do list. Start with brush your teeth, and do things so you have routine.’

I came off that canoe trip with nothing in my pocket and drove from Florida to New Orleans and back to drop off a canoe. And time just made no sense. I was so in tune with nature after the 233-plus days that if you put me in a room, I was hearing frequencies and things that would that make other people think—and other people were thinking—well, that I was crazy.

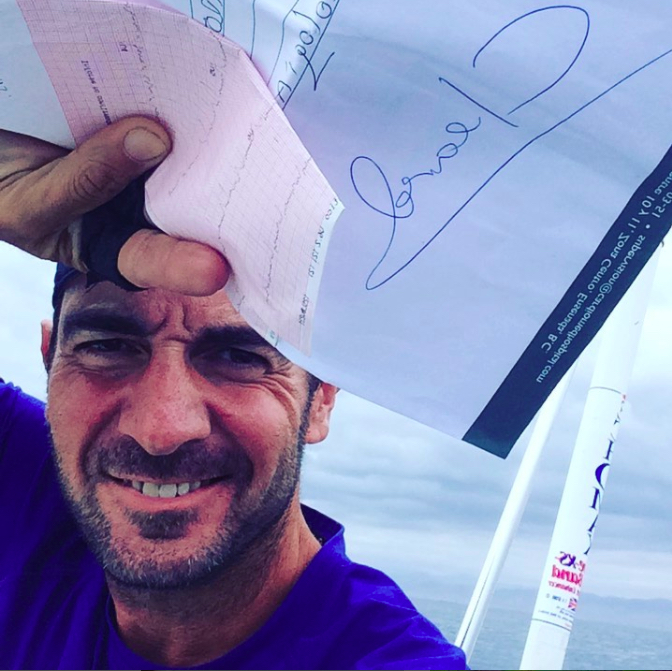

Carotta in lively weather on his first leg out of San Diego, a 36-hour run to Ensenada, Baja California.

You either follow up with another adventure, or you really have to hone in on your routine.

So I ended up working in media for the first time after a decade of self-producing everything. I was a morning reporter for a news station in the U.P. [Michigan’s Upper Peninsula] and I loved it. I found myself sharing other people’s stories, and unfortunately it just didn’t work out. All the people I met loved me, but it came with politics and behind the scenes I was doped.

I dug for answers, all the while being followed for a year. One hundred and twenty-thousand miles I drove in a year, up and down the coast, calling 9-1-1 seven times, being followed by white hats, black hats and gray hats. And if you ever want to find out who’s who, go to a nude beach like I did in New Smyrna Beach and you’ll tell when the Feds walk in with their clothes on. So that all came crashing down and I found myself in New Smryrna Beach, I had fainted, passed out or something, and was released from the hospital within six hours of that still hallucinating on whatever was in my system.

So to get right, you needed another adventure? That’s the cure for postpartum adventure—to get back out there. Is this ocean row is your first big expedition since the canoe trip?

Yes. It’s the longest one I’ve ever done, and I’ve done them for 10 years. I went around the world without a bag in 2010 for 50 days to experience minimalism, but I hated the ocean. I feared it. That’s where this experience comes from. I’m finding beauty in tackling things that I fear. I don’t fear much anymore, so this was really the one.

I left October 10th I think, from San Diego and I’ve spent half of the time on land fixing things with three stops, and the other half at sea. And I’ve never been dealt anything by God that I can’t handle.

And in fact, when I got to the point where I was pushed 250 miles offshore, the boat and everything was great, the mechanics were great. But the [contrary] winds were constant and I found myself running out of food. It was at a point where I couldn’t feel my legs anymore. They were numb because my body was eating itself, but it allowed me to connect, and if I was going to go it would have been my time. It wasn’t one of those luck things like many are going to categorize it as. I’m on the right path still.

Weeks after his supplies were exhausted, Carotta received a food drop from the Emerald Spirit. The Bahamian flagged, Indian-crewed tanker gave him supplies for 14 days, plus beer and a pack of smokes.

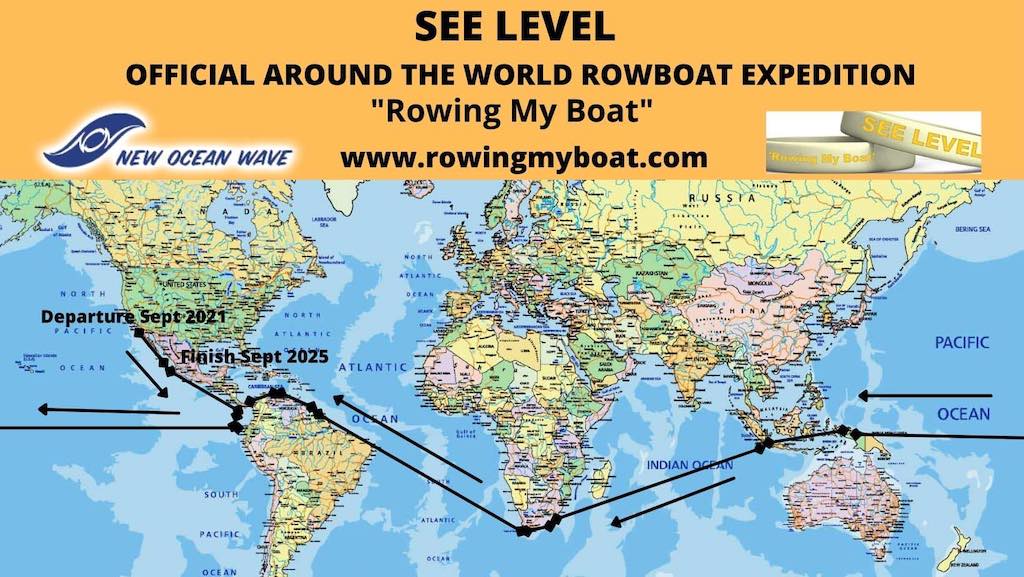

So this experience hasn’t deterred you from rowing around the world, even though a 200-mile crossing from Los Cabos to mainland Mexico took you more than a month and almost killed you. Now you’re talking about the Pacific, which is the biggest ocean crossing out there, I don’t even know how many thousand miles is it from Panama to . . .

. . . Ten thousand eight hundred miles. From Panama to New Guinea is 10,800 miles. That’s fair, Jeff. That’s the case, and that’s why no one’s done it.

I could have easily shipped this boat to Panama, which is the only circumnavigational point to do this route because you can’t row back up to the States, period. You can’t leave from the Gulf and get back to the Gulf. You can’t leave in San Diego and get back to San Diego. So I decided that this was the trial phase, and that’s exactly what it is—learning the boat. I had no experience. But this is the way I learn the best. Hands-on.

I felt the same about the Sea of Cortez. It’s only two hundred miles. But the currents are a major player when it comes to ocean rowing. These coastal runs don’t really get credit, because they’re like hitting a needle in a haystack. When you cross the Pacific, you have a wider range until you get closer to the destination.

I had discussions with Ed Gillet by coincidence. You know, I think you remember the guy who kayaked to Hawaii?

Of course. Ed Gillet is a legend. And you said you ran into him? Nobody runs into Ed Gillet.

I was at the police docks in San Diego for 30 days waiting to launch, and he came up to me and asked about my boat. He had me on his [sailing] boat for the evening and we talked shop and it was just awesome. He’s the one who told me about the currents and that they’re a real battle. A real battle. The whole point of my route that Chris Martin and I have come up with is that it’s doable because of the currents and the timeline of the winds.

Exactly. Over the years I’ve covered a lot of ocean rows, and they’re always a long crossing with the current and prevailing wind. I’ve never heard of anyone skipping down the coast the way you went down the coast of Baja. It seems like a risky way to get started, because every time you come close to land in an ocean rowing boat it’s a roll of the dice.

Every time I had a problem, Jeff, it was when I was land-based or anchored. You know, I had a heart attack in Ensenada.

What?

When I arrived on land. Yeah. I started the journey with a gal who is a Marine and was cutting hair. My buddy said he was going to fly to San Diego and join me, because the boat is a two-seater and I’ve always offered it up. But for whatever reason, when he showed up, he bailed. So we went and got a haircut and got a beer down on Little Italy street and the gal that cut his hair was like, ‘I’d really love to check out the boat.’ She said she wanted to go, and I said, ‘Let’s go.’

She was seasick the entire time, but when we arrived, we went to lunch and I had chest pains. And the next thing I know, I passed out and I was rushed to the cardiologist and three different doctors, and it turned out everything was clear. So the shock from the diet that I was on, going from noodles to tacos and beer, it didn’t adjust well and that was the first red flag for me. It happened again when I hit Cabo. I was dehydrated from what I believe is the dead salt water that you’re drinking when you desalinate it, and I passed out twice in McDonald’s in Cabo. I was woken and the medics were there and realized that my body needs way more water. So I’ve been checked out. Everything is fine. You know, I am 44, so things aren’t really moving the way they should.

I have to focus on those things, and that includes food. I should have had way more food. And I learned now of Costco offering these barrels that really are 30 to 90 days worth of stuff, so that’s my next go-to once I raise some more money.

Carotta in Ensenada with his hospital release papers. He suffered a heart attack less than two days into his planned round-the-world row.

So, wow. There’s a lot to unpack there. You’re rowing down the coast of Baja and you had a heart attack at your first landfall in Ensenada. You passed out again at your third landfall in Los Cabos. And then you ran out of food on your next crossing and must have been, what, three weeks with very little to eat?

Well, it sounds a lot worse than it is. Land is really where the problems happened. When I was anchored in Bahía Asunción the anchor broke and the boat washed ashore and that rudder finally snapped. So that’s when I got it replaced. And you know, it allowed me to connect with the community.

One of the locals gave me a chicken, so I took the chicken with me on the boat and I was going to use the eggs for nutrition and then pay it forward to the local community when I hit Guatemala. I called her Red. She was a great companion, a really light relationship that kept me positive. But when it came to day 26 and probably 27, I was on my final two servings of food. I had calculated it to five hundred calories intake and I had two servings left. So I had the chicken, and that’s when things started to really hone in on me.

My whole thought process was that I can’t lose my boat. I can get this done. I’m probably going to be in a real small corner when I say this, but I don’t believe personal adventurers should use the resources of these government agencies. I don’t want to burden them. Chris was like, ‘You have to get a tow.’ And I couldn’t afford a tow because it would be thousands of dollars.

At that time, one of the cruisers had already called the U.S. Coast Guard worried about me. They reached me and I told them, ‘I’m good man, I got this.’ The Coast Guard located a cargo going by, and they were more than happy to do a food drop. That was humbling and very hard to do, but it was also a moment where we connected. I connected with those guys from the Emerald Spirit and they did the food drop. When I say food drop, it was like Christmas had come since I was in the water for Christmas. And these white bags of everything you can imagine, you know, and they were just like, ‘Pay it forward, go and do it.’

They asked me how many days I needed it, and I said 10 to 14 to be safe. It was all Indian vegan food, which was great, and they also gave me a 12-pack and a pack of cigarettes. I don’t smoke, but that was my first day. Then I got rid of all the habits and carried on.

At that time, the compound lists of items on the vessel were adding up. The bearings on the [sliding] seat were so rusted that they wouldn’t turn, so I didn’t have the seat. There was a leak in the bilge so the boat was running with a lot of water in it and made it really hard to row. And to top it all off, when I tried to adjust the billing with my sat phone provider I couldn’t get a call back, and they cut the service.

When they do that, it says you can still make emergency calls only. Well, I tried to do the emergency calls. I tried to press S.O.S. because 14 days after [the food drop] the food was exhausted. I had 65 miles left and I wasn’t going to get there. I fired nine flares around New Years and no one stopped. The solar wasn’t allowing the plotter and desalinator to work. My VHF has a cable that you plug into a cigarette lighter. Those cables, I know now, are more important than the actual device. And when those were morta, I no longer had VHF. So now I’m down to my AIS [position transponder] and I’m typing my name on the AIS as I’m in distress.

Carotta’s planned journey will take him around the world, via the Pacific, the Indian Ocean around the Cape of Good Hope, and the South Atlantic back to the Caribbean.

So to sum up, everything on board had malfunctioned. You had no communications gear, you were out of food again, and your boat was taking on water. How did you get out of that pickle?

Luckily, I had my SPOT device. I activated it and I think that put out a call. But at that time the winds actually became in my favor for the first time in the entire 36 days. I started drifting to shore and I was home free. And as I’m going a Ukrainian ship and another one approached me. The final one, I think they were Italian. They gave me cheese and wine and chocolate, but they also said, ‘Listen. We have to hold you here because the United States Coast Guard is wondering where you are.’

That was about 2 a.m., and within an hour a small Mexican navy boat showed up. They followed me for two or three hours and then at 7 a.m. when the sun came up, they came flying out up to me in a Zodiac, saying ¿Qué Tal? ¿Qué Tal? What’s happening?

I told them I’m fine, but at that point they felt the firm need to support me. They said, ‘Aaron, we’re going to help you. You can keep your boat. We’ll tow it back.’ So I accepted at 63 miles out, and they put me in this town, Zihuatanejo, the one I was calling for. They’ve been so helpful.

And all of that still didn’t put you off ocean rowing? You’ve said you won’t quit, but what’s next? How will you get Smiles seaworthy and provisioned?

I was able to source a local boat builder who is fixing the boat. I was on pins and needles, because we worked for four hours to get it on land with a winch. The bill came in at 3,000—and that’s pesos [US$146]. So I lost my poker face at that point, was high-fiving and knew that $150 to get two rudders and all the fiberglass work done top-notch was going to be the best news I could find. I still didn’t have it, but hey, here we are and this is meant to be.

I’m getting sorted. I can breathe, I can rehydrate, I can learn from the experience, and I’ve connected to God on a purpose of this journey that is unstoppable. And I just think if I can figure out the best way to not involve others as much in the risk factor of things and connect the community with the storylines that they’re doing, everything is more than a blessing.

Even if you can get the boat squared away, you’re going to need food for what, half a year?

Three hundred days.

That’s a big ask with no money. How do you plan to keep going? I’ve tried to open the door and not be the door this time. The crowdfunding is set up to allow people to support me. For example, I put something up for Marcos, the boat builder. Any money that comes in goes to him, but fixes my boat at the same time. And anything over that is in support of him and his family for his humble hard work.

The goal was 20 grand to cover the trip costs, and I live on zero dollars. Right now there’s 37 hundred dollars in there, and there’s been 37 different donors. A lot of people in the first world aren’t really familiar with how far $100 can go and the difference that they can make. So what I do is actually hand that to him on camera on their behalf, so they can connect as a donor. I think that I’m onto something, so I’m going to go with that for now and try to eliminate the business expectations and see if the spirituality kicks in. I’m kind of leaning on that.

When you did your river trip years ago, we talked about river angels—people who help travelers on the river, who give you advice and pass you along to the next angel downstream. On the Pacific though, you’ll be alone for six to nine months. How will you transition from personal connection of the river and coast, to the monastic isolation of the ocean?

The big timeline makes six months seem like nothing, and I’ll be hopping when I cross the Pacific to 10 different islands and hitting all those small communities that you can only often hit when you’re in a rowboat. And the one thing about the river angels and the salt angels, as I call them, is that if you’re prepared to die in your own personal journey—which as Mr. Adventure or whatever you call yourself you should be—then humanity will either kick in or it won’t. That’s not for me to decide, and I trust it. If it’s my time, I don’t wish it, but I’m prepared. It’s been a beautiful time and there’s no way in hell I would ever stop, you know?

Aaron I’m not sure quite how to phrase this. The way your trip has gone so far, if you start west from Panama there’s a good chance you won’t make it to the other side.

What you’re voicing is what everyone voices, and it prevents them from doing things that they fear. I am connected with a purpose, and to me it’s defined in the Beatitudes as seeing. That’s why I call the journey See Level, because I am communicating what the world is as I see it. And I’m also in light of my Creator in the sense that it’s not up to me to decide if any of that happens. I follow all the rules and safety that I need to do, and I’m learning everything I can and taking the right advice. I don’t think that should prevent me from continuing, and if something does happen like that I hope people know that I lived exactly what I wanted to do, and I’m very happy with it.

All photos courtesy Aaron Carotta.